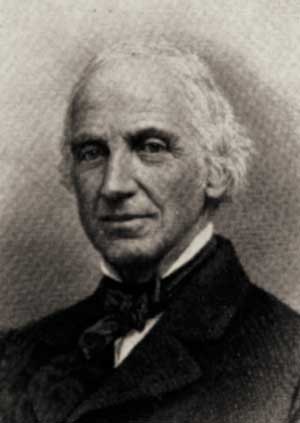

Edward Jarvis

Edward Jarvis

(1803–1884)

Edward Jarvis, the third president of the American Statistical Association, was born January 9, 1803, in Concord, Massachusetts, as the fourth of seven children born to Deacon Francis and Millicent (Hosmer) Jarvis.

Jarvis lived at home until he was 16 years old and attended the town school. He was thought of as a good student, learning geometry and trigonometry by the time he was 13.

Throughout boyhood, Jarvis was interested in mechanics. At 16, he took a job in a wool factory in Stow, where he remained for 18 months. The proprietor of the factory told Jarvis’ father that his son was a faithful worker, but his heart was in his books. Therefore, Jarvis entered preparatory studies at the Westford Academy and went on to Harvard College in 1822, where his interests were chemistry and botany.

Jarvis maintained good grades and, while at Harvard, taught school during college winters and after graduation. During his senior year, he left college to care for his brother, Charles, who suffered from a lumbar abscess. When Charles died four months later, Jarvis returned to college, only to be called home for his mother’s death. He finally graduated with the class of 1826—of which he was secretary for more than half a century.

After graduating, Jarvis taught at a school in Concord while living with his father. In 1827, he began studying physiology and anatomy with Josiah Bartlett and subsequently became a student of the elder Lemuel Shattuck, one of the able vital statisticians of the period. Jarvis practiced among the poor families that were then clustered in the western portion of Boston. He attended the required courses at Massachusetts Medical College (now Harvard Medical School) and also the medical courses for a year at the University of Vermont, where he was a student assistant in anatomy.

Jarvis graduated from Massachusetts Medical College in 1830 and began general practice in Northfield, Massachusetts, where he was moderately successful until 1832. He then moved back to Concord, where his interest in vital statistics began. On January 9, 1834, Jarvis married Almira Hunt, who became his constant assistant in the treatment of insane patients.

In 1837, at the suggestion of New England friends, Jarvis went to Louisville, Kentucky, where he engaged in general practice until his return to Dorchester, Massachusetts, in 1843. While there, he frequently contributed to the Louisville Medical Journal, corrected medical abuses in the Marine Hospital, and aroused interest in the establishment of a historical library. Though his financial success in Louisville was greater than it had been in Massachusetts, his antipathy to slavery and fondness for New England people and customs eventually induced him to return.

While in Kentucky, Jarvis became interested in insanity, however, and opened his home for the treatment of the insane. He was so successful that he began to devote all his time to this branch of medicine and was in demand by other physicians for consultation purposes. Jarvis was officially connected with the Institution for the Blind and the School for Idiots in South Boston. For many years, he held the title of superintendent for the School for Idiots.

His interest in anthropology and vital statistics led him to an analysis of census statistics. In studying the returns of the census of 1840, he was astonished at the large amount of insanity appearing among free blacks. He attributed this largely to carelessness in the compilation since some towns, which had no black population, were reported as having colored lunatics. He immediately presented the facts as he saw them to the American Statistical Association, which asked Congress to amend the returns. Congress refused to correct the enumeration, but Jarvis’ statistical abilities were brought to public notice. In 1849, the superintending clerk of the census of 1850 consulted him frequently and Jarvis wrote hundreds of pages in answer to these inquiries.

Jarvis was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in April of 1854. He made a sanitary survey of Massachusetts and published a report in 1855. Subsequently, by appointment of the secretary of the interior, he tabulated the mortality statistics of the United States as reported in the census of 1860, his work constituting half of the fourth volume of the reports of the eighth census. In 1869, he was asked to report a plan for the ninth census to the House Committee on the Census. His suggestions were received well and many were incorporated into the committee’s report to Congress.

In 1854, Jarvis was appointed a member of a lunacy commission to look into the number and condition of the mentally ill in Massachusetts and the necessity for a new insane asylum. To ensure the best possible study, he traveled to England and France, visiting asylums and attending the International Statistical Congress in London. He made a thorough survey and prepared a 600-page report that resulted in an appropriation for a new hospital. In 1863, he was appointed to inspect U.S. military hospitals.

Jarvis was the author of 175 printed speeches, articles, and pamphlets; two books on physiology, Practical Physiology (Philadelphia, 1848) and Primary Physiology for Schools (1849); and two manuscript histories of Concord. He wrote a 348-page autobiography that he gave to the Harvard College library. He also wrote extensively for medical magazines and other periodicals on physiology, vital statistics, sanitation, education, and insanity. Through correspondence and exchange with other statisticians in the United States and abroad, he collected one of the best statistical libraries in the country, most of which he gave to the American Statistical Association.

Jarvis had a stroke in 1874 from which he recovered slowly and only partially. After the stroke, he was unable to focus, but gradually began compiling materials on the history of Concord. He died of paralysis in Dorchester on October 31, 1884. His wife died three days later and the two were buried in one grave in their native town of Concord.