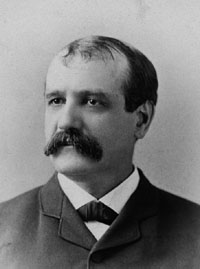

Francis Amasa Walker (1840–1897)

A Pioneer with Everlasting Energy

“General Walker considered each and every one of them [his public offices] a trust to be administered with integrity and with courage. He received degrees from more institutions of learning than any living American.” – Carroll D. Wright, 1897

Francis Amasa Walker was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on July 2, 1840. He died there on January 5, 1897. While alive, he fulfilled the roles of son, student, soldier, teacher, husband, father, professor, administrator, statistician, and author. He was the youngest child of Hannah (Ambrose) Walker and Amasa Walker, who was a prominent economist, Fellow of the American Statistical Association, and ASA vice president from 1860–1875.

Francis Amasa Walker was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on July 2, 1840. He died there on January 5, 1897. While alive, he fulfilled the roles of son, student, soldier, teacher, husband, father, professor, administrator, statistician, and author. He was the youngest child of Hannah (Ambrose) Walker and Amasa Walker, who was a prominent economist, Fellow of the American Statistical Association, and ASA vice president from 1860–1875.

When Walker was seven years old, he began studying Latin at a school for boys. He completed his college preparation at the age of 14 and spent another year studying Latin and Greek at the Academy at Lancaster (New England Normal Institute). He began attending Amherst College at the age of 15 and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in 1860. He was awarded both the Sweetser Essay Prize and the Hardy Prize for extempore speaking. After graduating, he joined the law firm of General Charles Devens and Senator George Frisbie Hoar to begin studying law, but eventually abandoned that endeavor to enlist in the Union Army.

Walker aggressively pursued a commission through Devens, commander of the 15th Massachusetts Regiment of Volunteers. At first, Devens was hopeful of commissioning Walker, so Walker ordered a lieutenant’s uniform in preparation. Unfortunately, Devens later had to tell Walker that the position had not materialized. Devens did have a Sergeant-major’s position, but made it clear he had never commissioned an enlisted soldier. Walker decided to accept the Sergeant-major position, regardless, and had his uniform changed. He was appointed Sergeant-major of the 15th Massachusetts Infantry on August 1, 1861.

The enlisted rank lasted just a few weeks, according to an entry in Walker’s diary:

On August 11, 1862, Walker advanced again to Major and Adjutant General of the 2nd Corps. His staff officer duties began on January 1, 1863, as Lieutenant Colonel, serving Generals Couch, [Winfield Scott] Hancock, and [Gouverneur K.] Warren. He fought with the Army of the Potomac in more than a dozen Civil War battles, including Chancellorsville, where he was severely wounded by a shell on May 1, 1863.

On August 1, 1864, Walker was promoted to brevet Colonel. Shortly thereafter, on August 25, 1864, he was captured at Reams’ station by a picket of the 11th Georgia. A day later, aided by the cover of night, he and Captain James G. Tripp of New York attempted to escape just below Petersburg, Virginia, by crossing the Appomattox (James) River. Tripp could not swim, so Walker made the voyage solo. Unfortunately, he swam upstream and was recaptured by the 51st North Carolina. When asked why he didn’t drift downstream, he maintained he was completely dominated by the common saying that “to cross a river, one must head upstream.” His capture and confinement in Libby prison ruined his health and forced his retirement from the military.

Out of the military, Walker taught Latin, Greek, and mathematics at Williston Seminary in Easthampton, Massachusetts. In August of 1865, he married Exene E. Stoughton, the oldest daughter of Timothy Morgan Stoughton from Gill (Turner’s Falls), Massachusetts. Together, they had seven children—Stoughton, Lucy, Francis (a third-generation economist), Ambrose, Eveline, Everett, and Stuart. Early in 1868, he became assistant editor (and later chief editorial writer) of the Springfield Republican Newspaper, teaching by day and writing by night. While at the paper, he wrote Commerce and Navigation of the United States. Near the end of 1868, he was offered a teaching position at Amherst College (to take the place of his father).

In January of 1869, Walker accepted the position of Chief of the Bureau of Statistics and Deputy Special Commissioner of Internal Revenue. He was confirmed Superintendent of the Ninth Census in 1870 and began devising new methods of presentation and producing a statistical record worthy of a nation of 40 million people. While holding this position, he was appointed U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs and, later, as commissioner to the International Monetary Conference at Paris. He had no knowledge or experience in Indian affairs, but wanted to see the 9th Census come to a close under his directorship, so accepted the appointment with no monetary remuneration. By the time he resigned, he was able to write The Indian Question, which became a standard treatise.

Walker also held the chair of political economy and history in the Sheffield Scientific School of Yale from 1872 to 1881. During this time, he not only received his master’s degree from Yale (1873) and PhD from Amherst College (1875), he lost his father (1875), was awarded the Medal of the First Class by International Geographical Congress of Paris for his editorship of The Statistical Atlas of the United States (1874), and was elected an honorary member of the Royal Statistical Society of London (1875).

By the time Walker was elected a member and Fellow of the ASA, he was appointed Chief of the Bureau of Awards at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876—a truly daunting task. For his efforts, he was recognized formally by Sweden, Norway, and Spain. He lectured at The Johns Hopkins University between 1877 and 1879, but declined a professorship, thus publishing the first course under the title of Money (1878). In 1878, the National Academy of Sciences elected him an honorary member.

Walker’s recognition as Chief of the Bureau of Awards at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876 resulted in an invitation from President Hayes urging him to accept the position of Assistant Commissioner General for the Paris Exposition of 1878. The United States also received an invitation to participate in the International Monetary Conference in Paris. Walker served as a delegate to that conference in addition to the exposition, International Monetary Congress, and to a special conference called to consider a Franco-American Treaty of Commerce.

Walker was actively interested in the progress of common-school education and the introduction of mechanical training into its curriculum. As such, he was appointed a member of the School Committee at New Haven from 1877 to 1881 and a member of the Board of Education of Connecticut from 1878 to 1881. In 1879, he gave 12 lectures at the Lowell Institute, Boston, and published Money in Its Relations to Trade and Industry. He was a trustee of Amherst College from 1879–1889. In April of 1879, President Hayes appointed him superintendent of the 10th Census, which was referred to as the “Jumbo of Censuses” because it had 22 volumes in addition to the index. Walker resigned from the directorship of the 10th Census and accepted his appointment as president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the winter of 1881, when he determined he would steer MIT to distinction among contemporary learning institutions.

In addition to his MIT presidency, Walker served as a member of the Board of Education of Massachusetts from 1881–1890. He received an honorary degree of Doctor of Law from Amherst College and Yale in 1882 and lectured two courses at Harvard in 1882 and 1883, which later appeared in book form as Land and Its Rent. He received an honorary degree of Doctor of Law from Harvard in 1883 and lectured another course there in 1896. Senator Leland Stanford unsuccessfully offered Walker the amount of his MIT salary to become the first president of Stanford University, but Walker didn’t accept.

Aside from his statistical and historical publications, Walker was an extensive writer on political economy; his works greatly influenced economic thought in Europe and America. He wrote numerous articles and books about American economics and pioneered the use of statistical numbers to illustrate economic theories. His love of history resulted in membership in the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1883.

In January of 1883, Walker became the fourth president of the ASA—an office he held until his death in 1897. During this time, he was elected Commander of the Massachusetts Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States and chairman of the Massachusetts Topographical Survey Commission. He also served as the president of the American Economic Association, which strengthened the ties between it and the ASA. Before the Nobel Memorial Prize was created, the Walker Medal was awarded every five years to an established economist for his or her lifetime work. In 1885, Walker became a member of the International Statistical Institute, which he helped form. On the home front, he was elected a member of the School Committee of Boston in 1885 and remained so until 1888.

Walker had an all-encompassing year in 1886. He completed History of the Second Army Corps and was made an honorary member of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers and senator of Phi Beta Kappa. He received an honorary degree of Doctor of Law from Columbia University in 1887 and from St. Andrews, Scotland, in 1888. He authored the article “General Hancock and the Artillery at Gettysburg and Meade at Gettysburg” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War (Vol. III., 1888). He became correspondent of the Central Statistical Commission of Belgium and corresponding member of the California Academy of Sciences in 1888. In 1889, he was made an officer in the French Legion of Honor and completed First Lessons in Political Economy.

He was a vice president of the National Academy of Sciences from 1890 until his death and a member of the Park and Art Commissions of Boston from 1890–1896. He was also vice president of the Military Historical Society of Massachusetts from 1891 until his death. He was chairman of the Massachusetts Board of World’s Fair Managers from 1892–1894 and vice president of the American Society for the Promotion of Profit-Sharing from 1892–1897. In 1892, he received an honorary degree of Doctor of Law from Dublin, Ireland, and was made an honorary member of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester, England. He held the office of vice president of the Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers from 1892 until his death, along with correspondent of the Institute of France from 1893. In 1893, he was named honorary president-adjoint of the International Statistical Institute.

In 1894, Walker authored “Life of General W. S. Hancock” in the Great Commanders Series, was awarded an honorary Doctor of Philosophy degree from the University of Halle, and made a corresponding member of the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

In 1895 and 1896, he completed The Making of the Nation and International Bimetallism. He was awarded another honorary degree of Doctor of Law from Edinburgh, Scotland, and became a trustee of the Boston Public Library.

Editor’s Note: Information for this article was taken from “A Life of Francis Amasa Walker” by James Phinney Munroe; “Francis Amasa Walker” by Carroll D. Wright; The Civil War Home Page, www.civil-war.net; and The 15th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry in the Civil War 1861–1864.

Additional Reading

- The History of Economic Thought Website, http://www.hetwebsite.net/het/profiles/walker.htm

- James Phinney Munroe, J.P. 1923. A Life of Francis Amasa Walker. New York: Henry Hold & Company.

- Newton, B. 1968. The Economics of Francis Amasa Walker: American Economics in Transition. New York: A. M. Kelley.

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 1897. Meetings Held in Commemoration of the Life and Services of Francis Amasa Walker. Boston.

- Hawkins, E.L. 1892. An Abstract of Walker’s Political Economy. Oxford: A Thomas Shrimpton & Sons; London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co.

- Parrington, V.L. “Francis A. Walker” in Main Currents in American Thought. New York: Harcourt, 1958

- Harnwell, Susan L. “Francis Amasa Walker,” www.nextech.de/ma15mvi

- 1877. “Walker’s Wages Question.” North American Review.

- 1883. “Review of Political Economy.” Atlantic Monthly.

- 1884. “Review of Land and Its Rent.” New Englander and Yale Review.

- Kopf, E.W. 1924. “Life of Francis A. Walker by James Phinney Munroe.” Journal of the American Statistical Association, 19(148):554-555.

- FitzPatrick, Paul J. 1957. “Leading American Statisticians in the Nineteenth Century.” Journal of the American Statistical Association, 52(279):301-321.

- Wright, Carroll D. 1897. “Francis Amasa Walker,” Publications of the American Statistical Association, 5(38):245-275.

- Cord, Steven B. 2003. “12 Walker: the General Leads the Charge – Part III: Nineteenth Century Americas Critics.” American Journal of Economics and Sociology.

- F. A. Walker Bibliography and Links at McMaster University Archive

- Francis Amasa Walker: Biographical Note: Institute Archives & Special Collections: MIT

- Biography of Walker at U.S. Census

- 1870 Census of Population and Housing, www.census.gov/library/publications/1872/dec/1870a.html

- F. A. Walker [1407] Amherst College Biographical Record: Class of 1860

- JSTOR, Journal of the American Statistical Association and Publications of the American Statistical Association

Books by Francis A. Walker

- The Indian Question, Boston: J. R. Osgood & Company, 1874 (388k – from University of Michigan Library)

- The Wages Question: a Treatise on Wages and the Wages Class, New York: Henry Holt & Company, 1876 (979k – from University of Michigan Library)

- History of Pauperism in Massachusetts, Boston: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Dept. of General Studies, 1892, ix, 237 pp. [Thesis (B.S.)]

- International Bimetallism, New York: Henry Holt & Company, 1896

- General [Winfield Scott] Hancock, New York: D. Appleton, 1894

Articles by Francis A. Walker

- 1869. “American Industry in the Census.” The Atlantic Monthly, 24(146):689-701.

- 1870. “What To Do with the Surplus.” The Atlantic Monthly, 25(147):72-86.

- 1873. “The Indian Question.” The North American Review, 116(239):329-389.

- 1873. “Our Population in 1900.” The Atlantic Monthly, 32(192):487-495.

- 1875. “The Wage-Fund Theory.” The North American Review, 120(246):84-119.

- 1875. “Growth and Distribution of Population.” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, 51(303):391-415.

- 1875. “Our Domestic Service.” Scribner’s Monthly, 11(2):273-278.

- 1880. “The Principals of Taxation.” Princeton Review, 2(1):92-114.

- 1882. “American Agriculture.” Princeton Review, 1(1):249-264.

- 1882. “The Growth of the United States.” The Century, 24(6):920-927.

- 1883. “The Growth of the United States.” The Century, 25(3):462.

- 1883. “Henry George’s Social Fallacies.” The North American Review, 137(321):147-158.

- 1885. “Shall Silver Be Demonetized?” The North American Review, 140(343):489-492.

- 1887. “Socialism.” Scribner’s Magazine, 1(1):107-119.

- 1887. “General Hancock and the Artillery at Gettysburg.” The Century, 33(5):803.

- 1887. “What Shall We Tell the Working-Classes?” Scribner’s Magazine, 2(5):619-627.

- 1889. “Regimental Losses in the American Civil War, 1861–65 by William F. Fox.” [review] Publications of the American Statistical Association, 1(5):214-216.

- 1890. “Mr. Bellamy and the New Nationalist Party.” The Atlantic Monthly, 65(388):pp. 248-263.

- 1890. “The Eight-Hour Law Agitation.” The Atlantic Monthly, 65(392):800-811.

- 1890. “Statistics of the Colored Race in the United States.” Publications of the American Statistical Association, 2(11/12):91-106.

- 1891. “The Census of Austria.” Publications of the American Statistical Association, 2(16):444-449.

- 1892. “The Fall of the Rate of Interest and Its Influence on Provident Institutions.” Publications of the American Statistical Association, 3(20):255-259.

- 1893. “The Technical School and the University.” The Atlantic Monthly, 72,(431):390-395.

- 1896. “Restriction of Immigration.” The Atlantic Monthly, 77(464):822-830.

- 1897. “Remarks by President Walker at Cosmos Club in Washington, DC, on the Evening of December 31, 1896.” Publications of the American Statistical Association, 5(37):179-187.

- 1897. “The Causes of Poverty.” The Century, 55(2):210.