A Wake-Up Call to Statistical Consultants

Jonathan J. Shuster, Department of Health Outcomes and Biomedical Informatics, College of

Medicine, University of Florida, and Chris Delcher, Department of Pharmacy Practice and Science,College of Pharmacy, University of Kentucky

This is a summary. The full report is available to download as a PDF.

Based on a random survey of American Statistical Association members by Min Qi Wang, Alice F. Yan, and Ralph V. Katz discussed in the Annals of Internal Medicine paper, “Researcher Requests for Inappropriate Analysis and Reporting: A US Survey of Consulting Biostatisticians,” one can infer that surprisingly many collaborator (client or colleague) requests for analysis should have aroused suspicions of possible misconduct. The goals of this follow-up analysis, using the actual survey data supplied by Katz, are to answer the following questions:

- How many ASA members have received at least one of three specific inappropriate requests (cited below) in the past five years?

- How many episodes of these requests collectively occurred in the past five years?

Neither the Wang et al. article nor the accompanying editorial by A. Russell Localio, Catharine B. Stack, Anne R. Meibohm, Eric A. Ross, Eliseo Guallar, John B. Wong, John E. Cornell, Michael E. Griswold, Steven N. Goodman, titled “Inappropriate Statistical Analysis and Reporting in Medical Research: Perverse Incentives and Institutional Solutions,” addressed these critical questions.

Briefly, the results of our analysis conservatively suggest more than 1,800 ASA members, covering more than 3,000 episodes in the past five years (or 600 episodes per year), have received what some may call “nefarious-looking” requests because they seem to be intended to deceive.

To illustrate the potential severity of these numbers, consider that, in 2017, the Office of Research Integrity (ORI) received 215 new cases (phone, email, or institutional) that may have qualified as nefarious-looking. Even if half the consulting cases merit reporting to ORI, funder of the Wang at al. study, this would more than double their caseload.

Given the magnitude and implications of our estimates, we recommend new procedures for consultants, their institutions, and the ASA to follow to help maintain a high level of integrity for statistical science. The full report also contains a Google survey we conducted of the 1,558 ASA members about their opinions of the consultant’s responsibility when faced with such requests.

The Office of the ASA Executive Director provided the Wang team with a random sample of 4,000 ASA members. The team screened 126 of these members as ineligible because they were not primarily involved in biostatistical consulting or data analysis, leaving a frame of 3,874 members. By random sampling in 16 50-person batches of emails, the team requested a final sample of 800 members to complete the survey. Four hundred attempted to complete the survey, but 10 of these were excluded, leaving a final sample of 390.

The survey asked the respondent two questions about each of 18 scenarios of analytic requests they received for “inappropriate” action:

- Frequency in the last five years: 0, 1, 2–4, 5–9, or 10+ episodes

- The consultant’s perceived seriousness of the apparent “bioethical violation” on a scale of 0–5, with 5 being the most serious

In our judgment, only three of the questions would require immediate action to resolve possible misconduct.

The nefarious-looking questions: How many times in the last five years were you asked to (1) “falsify the statistical significance (such as p-value) to support a desired result”? (2) “change data to achieve the desired outcome (such as prevalence rate of cancer or other disease)”? and (3) “remove or alter some data records (Observations) to better support the research hypothesis”?

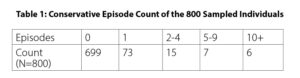

For the 390 who completed the survey, we impute an outcome for each question as 0, 1, 2 (if 2–4 episodes), 5 (if 5–9 episodes) and 10 (if 10+ episodes). Since, for each respondent, the same episode may be reported under multiple questions, we imputed the overall episode count conservatively as the maximum imputed response for the three questions. For the 410 members sampled who either refused to participate (400) or had a non-evaluable response (10), we conservatively imputed the response as zero. Table 1 gives the distribution of the 800 episode-count outcomes.

Projecting these data to the 17,400 ASA members, we conservatively estimate with 95% confidence that more than 1,800 members experienced more than 3,000 episodes in the past five years.

Implications for the Consulting Community

We view these estimates as unacceptably high and a wake-up call for action by all of us engaged in statistical team science. We must be more proactive to greatly reduce or eliminate this behavior—not only for our clients, but for the integrity of our profession. It is not appropriate for us to resolve suspicious requests in a vacuum without a thorough and discrete assessment by university or organizational ethics officers.

We are obligated professionally to reach out when faced with a request for aiding and abetting potentially unethical conduct. However, we must not make any direct accusations of intellectual misconduct on the part of our colleagues. View the full report to see how similar events are handled by the American Contract Bridge League, which governs Duplicate Bridge in North America. Similar systems could readily be adopted by the ASA.

Limitations

Our analysis has two limitations that are beyond anything mentioned in either of the parent articles. First, because the survey retrospectively requested respondents to estimate their five-year experience, respondents could well have had recall bias, especially with respect to number of episodes and whether they occurred within the five-year window. However, it seems likely that the estimate of whether the member had at least one of these potentially nefarious requests should be viewed as a still more conservative estimate of their career-long experience.

The second limitation is of greater concern. The questions seem to require an inference on the part of the consultant about the purpose of the nefarious-looking request. For example, if you were asked to remove or alter some records (an affirmative answer to the first part of Question 3), how does the consultant infer the purpose was “to better support the research hypothesis”? The ability of the respondent to understand intent seems uncertain at best.

The only thing that ASA could do is to ban the member and revoke any certification he/she has earned through ASA. However, the vast majority of statistical consultants are not ASA members, and many are not even statisticians to begin with: they can be economists, physicists, mathematicians, data scientists, or anything. The title of statistician is not protected, unlike lawyer or medical doctor, so anyone can call herself statistician.

It is not much different from academics who produce 200 papers a year. How can they possibly do it unless there is some fraud or unethical behavior? They just get they name added to a bunch of submitted articles that they have never even read (it goes this way: add my name in your article, I’ll add yours in mine), and they produce in bulk tons of articles that are just a new version of some old stuff, and in the process, statistical analyses are rushed, un-replicable, and faulty. At least, these professors could be fired for such behavior, though he won’t happen. But you can not fire an independent statistical consultant, even a fake one.

Finally, if you search for “statistical consultants” on Google, you will find a bunch of people advertising themselves as statisticians, and all they do is write your essays, PhD thesis or even academic papers, for a fee typically around $5,000. It’s just as unethical (for the client and service provider) but many have a genuine graduate degree in statistics (often a true PhD). They do this because they were never able to secure a job in Academia or elsewhere after completing their PhD, due to over-production of PhD’s by the Academia.