The Future of Statistical Publications

The ASA will celebrate its 175th anniversary in 2014. In preparation, column “175”—written by members of the ASA’s 175th Anniversary Steering Committee and other ASA members—will chronicle the theme chosen for the celebration, status of preparations, activities to take place, and, best yet, how you can get involved in propelling the ASA toward its bicentennial.

Contributing Editor

David Banks is a professor of the practice of statistics at Duke University. He was coordinating editor of the Journal of the American Statistical Association; editor of the Journal of Transportation Statistics; and associate editor for Statistical Methodology, the American Mathematical Monthly, STAT, The Electronic Journal of Statistics, and Environmetrics. He co-founded Statistics, Politics, and Policy; moderates the online repository arXiv; and referees about a dozen papers each year.

An anniversary that ends in ‘0’ is an occasion for celebrating the past. When one ends in ‘5,’ it is an opportunity to plan the future. In that spirit, and responding to an invitation from the 175th Anniversary Committee of the American Statistical Association, I urge that we re-evaluate our publication processes. Electronic media are transforming access to information; it is time for the ASA to decide how to manage this change.

I fear our current approach to publishing does not serve us well. It takes too long, so our best scientists are driven to other journals in faster disciplines. Refereeing is noisy and often achieves only minor gains. And the median quality of reviews is deteriorating due to journal proliferation, pressure on junior faculty to amass lengthy publication lists, and the slow burnout of conscientious reviewers.

Our present paradigm has other structural problems. Published articles are static—correction and improvement are impossible. Published research often does not replicate, which is hard to flag. Readers must reach too far to find the code behind the article, and the data are nearly impossible to obtain. Correct work that is not sufficiently novel is excluded and lost. And there is a large gray literature that cannot be easily accessed or assessed (e.g., federal reports, weighting schemes for official surveys, lecture notes, classroom exams, code documentation, data/metadata, PhD theses).

I am far from the first person to raise these concerns. Karl Rohe has a parable that illustrates many of these issues on Page 16. Larry Wasserman, Jim Pitman, Nick Jewell, Nick Fisher, and Roger Peng, among others, have grappled with various features of the problem. Since 2005, the ASA has formed three committees to study the matter; most recently, Len Stefanski is chairing one, which will make recommendations to the ASA Board in November. Among young statisticians, almost all perceive the inefficiencies of traditional publication and share a common sense of the improvements that are possible.

Change will happen. If we fail to plan ahead, the ASA will be forced to adopt whatever system Wiley or Springer or the American Mathematical Society establishes as the standard, but their interests and needs align imperfectly with ours.

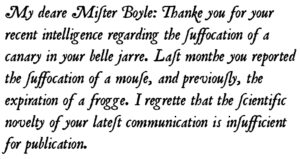

Today’s publication process was essentially invented by Henry Oldenburg, the first corresponding secretary of the Royal Society. He received letters from members describing their research, copied them out in summary form, and mailed those summaries to other members. But his hand grew weary, and he began to send notes of the following kind:

Given his technology, Oldenburg’s stringencies were essential. Printing and distribution costs were the limiting factors; pauca sed matura had to be the standard. An entire economic ecology grew up around those constraints: Publishers set type and sold volumes; societies created editorships and referees; and libraries emerged. Authors and editors created content for free and publishers made fortunes; this was the best solution possible. Until the Internet.

Now, we have fresh choices. Electronic articles can be living documents, as on arXiv; better versions layer on top of the old. Articles may use color and dynamic graphics and be as long as necessary, with detailed proofs and worked-out examples (while reader feedback enforces concision). Article quality can be signaled in multiple ways, either by conventional review or by ungameable rating systems, similar to page-ranking algorithms. Readers can use personalized recommender systems to discover papers. And data, code, and gray literature become easy to access. Space limitations prevent a full catalog of the possible features (and bugs), but I expect Stefanski’s report will be more comprehensive.

I invite readers to comment on this topic. Just post your thoughts below.

Very nice piece, David. To me, almost the only thing the current system still has in its favour is its ability to filter, albeit imperfectly. I am intrigued by your closing comment that this might be achieved by more algorithmic means and wonder if there is scope for ASA (or RSS in the UK) to commission a piece of work to investigate this – it ought to be amenable to statistical design and analysis.

I am concerned that searches of our future electronic literature will be as frustrating as Web searches. We have all had searches that yielded 3.2 million hits or merely 68,000 hits. Finding what we want is then still like finding a needle in a haystack. We will need some good Boolean logic input controls for searches to better limit the number of hits to the more relevant ones.

David, thank you for providing very insightful commentary or a critical topic. Timeliness, clarity and quality will be greatly enhanced by your recommendations, and it is my hope that the ASA considers these possibilities sooner rather than later. Technology used in this manner can be a boon to our profession.

David,

I never would have believed a decade ago that I could wind up pretty much agreeing with your views of the publication process. I was a vigorous advocate and defender of the traditional review system. But by now I’m convinced that it’s irreparably broken. Two decades ago I sweat blood as an Editor trying to be fair and constructive in how I handled people’s work, and to make sure that what appeared in the journal was worth reading … and expected that mentality to continue to be dominant. But in the broad it hasn’t.

Too many people now game the system and abuse it for short-sighted selfish purposes. As reviewers, they give members of their club a “pass” in the reviewing process, and use it to keep others out of their sandbox. “Double blind” is a joke. Referee reports are increasingly shoddily done, too often consisting of absolutely stock/mindless/meaningless “suggestions”/”criticisms” (like “your simulation could be bigger”). Too many Editors and AE’s don’t do their duty and actually read and think about submissions and how to improve them, but rather just shuffle reports. University promotion committees only know how to count, and young people are effectively encouraged to cheat (and gum up the system) by submitting the same basic idea in slightly different wrappers to multiple journals or by chopping a single story up into LPU’s. Too many Editors don’t actually want to see complete pieces of work, preferring easily handled short communications. And “good journals” are in no way immune to these trends.

I could easily be convinced to quit bothering to submit to even ASA journals. Let’s just put all on the web and let the buyer beware.

Best,

Steve

I completely agree with you David.

I think we should abandon journals completely and just

use arXiv.

We should eliminate refereeing completely and let the marketplace

of ideas decide the value of a paper.

Best wishes

Larry

David, thank you for the thought provoking commentary on where ASA publications might be moving. I agree that change to the system is needed, and the statistical community will benefit from it.

Something that’s not clear to me about this new ecology is the role of thoughtful, critical and constructive review, and its potentially positive impact on publications. As the current editor of Technometrics, I try very hard to avoid “just shuffling reports”. A large number of papers submitted to Technometrics benefit substantially from the review process. As initial submissions they may be unclear, unfocused or possibly incorrect. At the same time, they often contain a novel idea that needs to be communicated. Through critical assessment, these papers improve significantly, so that by the time they are published they are more accessible and understandable, and the approach and its impact is clear. Of course, a well-done review should also significantly improve the chances that the paper is correct. I believe that authors, especially less experienced ones, learn to think more critically about their work during such a process.

Constructive peer review could be compatible with the new, electronically mediated and open environment you envisage. In fact, I’d argue it is a key component of such an environment. A challenge will be to develop ways in which such critical thought can flourish and be recognized for the role it plays in moving research forward. For instance, there should be some way to document and assign “credit” to those who take the time to think critically about someone else’s work. If a reviewer contributes significantly to the improvement of a paper, and that paper is seen as important, some of that importance should be ascribed to the reviewer. In the current system, the authors tend to absorb most of the credit, while referees and AEs remain anonymous.

A mechanism for fairer sharing of intellectual credit might be more feasible in the new ecology you suggest, via automated bookkeeping and indices of importance (e.g. pagerank). It won’t be easy to develop such a system. For instance, harsh but justified criticism of an emerging work may be ultimately beneficial, but the critic may be reluctant to have their role made public, even if they stand to gain credit.

Hopefully the framework you envisage will improve those aspects of the publication process which are broken, while retaining the key element of thoughtful review.

Thanks David,

I think one of your most important points is that we risk being shimmed into a system that is even more mediocre. The current attempts for “academic publishing 2.0” are all VC backed ventures with for profit incentives. At times, their incentives will differ from our community’s and I am scared that we might end up in such a system.

My guess is that most academics are hesitant to sign up for the “facebook of science” when it is a for profit system. What we really need is an open source platform/protocol (i.e. something like the language S). Then, even if the mathematicians choose a venture that is different from the statisticians’ that is different from the economists’, so long as their different ventures choose to adopt or support the open source protocol, there can still be open communication between the fields.

In undergrad, I took a course on “social movements.” One of the key insights from that course was that the organizational structure for the civil rights movement bootstrapped on the already existing network of black churches. By bootstrapping the organizational structure, they avoided several “start-up” stumbling blocks. I wonder if there are enough R developers that would be interested in developing an open source protocol… Maybe python developers? Others? Thoughts?

The hope with such a protocol is that it would allow software producers to quickly develop new features that appeal to different communities, while at the same time ensuring that we are not all in separate islands. Furthermore, if the protocol had a mission statement that all plug-in’s had to adopt, then we could ensure that all communities follow a certain minimum of openness.

Another point… Many people have objections to “letting go of peer-review.” It might be good marketing if we emphasized how a new system could fully adopt the current system while fixing some of the bugs. For example,

1) in the current system, there isn’t much cost to a referee to provide a bad review (only embarrassment to the AE). The new system could provide a referee rating where after the AE has made a decision, the referees both rate the other referee’s response (this could be a useful metric in tenure decisions).

2) Furthermore, such a system could easily have a default where the referees discuss the paper in a forum with the AE (and editor, if she/he is interested).

3) Also, the referees could choose for their reports to be made public.

I am sure we could think of a whole bunch of other “features” that would improve the current system. The (marketing) emphasis here is that they are improvements, not a whole scale dumping and re-designing of the current system. Such considerations would be useful in designing a protocol.

In response to Larry Wasserman’s post that “We should eliminate refereeing completely and let the marketplace of ideas decide the value of a paper.”

Markets are most efficient when the actors have good information. The challenge is to provide a system that provides accurate and useful information. Simply posting papers on arXiv is too static. Only the author is awarded “openness.” However, it exists in a void that is difficult to navigate. It could be improved with discussion boards and some sort of curating (either through peer-review, community voting, or algorithmic content recommendation).

The structure of this discussion board is a good example of a system that fails to foster discussion… my response is not linked to your comment and you will (probably) not be informed that I have responded.

Topic: Quality and Filtering

Thank you all for your thoughtful responses.

Regarding quality and filtering, as raised by Peter and Hugh, and implicitly by Steve, I think the ASA has the luxury of choosing among many possible options, including options that allow pluralism.

Some authors may request at the time of submission that their article be treated as a standard paper for, say, JASA. It would undergo (slow) review and (lengthy) revision. If it is accepted, it would be tagged with a JASA quality stamp, and its text would be frozen forever, like an intellectual flower pressed within the pages of hardcopy publication models. And this is a fine option for those who want it.

Other authors may prefer an arXiv model, in which the paper is posted without review and read by any interested party, and the author may make changes in response to comments, so that the paper improves. In that case, quality might be assessed in several ways. Among the options the ASA could endorse are:

1. The quality of the paper is a function of the citations it receives, perhaps weighted according to the quality of the citing papers.

2. The paper might be rated by those who read it, on a scale from 1 to 10. The ratings of those readers should probably be weighted according to the quality ratings of their own publications, to reduce the ability to game the system. (I suppose a cabal of eminent statisticians might be able to tip the needle unfairly, but I don’t think that is a major concern—in many ways, they have the power to do that under the current system, if they want.)

3. Members of the ASA might be allowed to approve up to 5 papers per year, as a member perk. A ceiling of 5 would reduce the chance that someone will squander a good ranking on a bad (researcher) friend. Personally, I’m not keen on this, and would like to do some additional weighting at the least, but it might help engage the membership.

4. And there are other ways; e.g., combinations of these methods.

A third set of authors might post a draft paper and invite anyone in the community to contribute to its improvement. Massively co-authored papers would be bold and new. Perhaps Mike Jordan would post a germ of an idea in the morning, Dave Blei and David Dunson would add some flesh to its bones, Edo Airoldi would contribute an example, Evan Greif would add some simulations, Tamara Broderick would go over the proofs, I would run spellcheck, and within a short time, the profession would have an interesting new paper.

A nice thing about several of these models is that people need only contribute time and attention to papers that interested them. And the possibility for living documents, that improve continually in response to feedback, seems to me to go a long way towards answering the concerns that Hugh raised. Yes—review can improve a paper and be instructive (especially to new authors). I think several of these models allow that happen in ways that can work better than what we have now.

Best wishes,

David

Topic: Search

Wayne Nelson raised a concern about the ability to search in a sea of papers of uneven quality, especially given the difficulty of finding effectively discriminating keywords.

Certainly one could search in the usual ways, and modern web search is actually pretty good, imho.

But statisticians can do better. One approach is to use various tools from topic modeling and FREX plots to sharpen our relevance and precision; i.e., to ensure that nearly all hits are pertinent and nearly no pertinent papers are missed.

A second approach is more novel. When starting a search, one sees a two-dimensional scatterplot of all papers laid out according to the two major principal axes derived from latent semantic indexing (or one of its improved offspring) of the total corpus. As one types in keywords, irrelevant articles drop out (go dark) and the axes are recomputed according to the remaining articles. Without too many keywords, one would have a visualization in document space of all relevant articles and their relation to one another. For example, one might see three relevant clusters, and realize that one needs to check the content of each.

A third approach is to visualize the citation tree. Knowing which papers cite which others is a a great way to find papers relevant to one’s search.

I realize that most of this is science fiction. But I do think statisticians can bring special tools and perspectives to improving the ability of researchers to execute web search.

Best wishes,

David

David, you are probably right, but this development makes me sad. Call me old-fashioned, but having worked many years as editor, associate editor, reviewer and author, I prefer the printed articles in established journals. Most importantly, however, we teach our students about quality control, and in our own work are now saying that quality control is not important: The “market place” will take care of it. Good luck and best wishes from a retired professor.

David, you are probably right, but the development in the direction of electronic publishing only makes me wonder whether we are saying that quality control for our own work is not important, contrary to what we are teaching our students.

Welcome!

Amstat News is the monthly membership magazine of the American Statistical Association, bringing you news and notices of the ASA, its chapters, its sections, and its members. Other departments in the magazine include announcements and news of upcoming meetings, continuing education courses, and statistics awards.

ASA HOME

Departments

Archives

ADVERTISERS

PROFESSIONAL OPPORTUNITIES

FDA

US Census Bureau

Software

STATA

QUOTABLE

“ My ASA friendships and partnerships are some of my most treasured, especially because the ASA has enabled me to work across many institutional boundaries and

with colleagues from many types of organizations.”

— Mark Daniel Ward

Editorial Staff

Managing Editor

Megan Murphy

Graphic Designers / Production Coordinators

Olivia Brown

Meg Ruyle

Communications Strategist

Val Nirala

Advertising Manager

Christina Bonner

Contributing Staff Members

Kim Gilliam

Contact us

Amstat News

American Statistical Association

732 North Washington Street

Alexandria, VA 22314-1904

(703) 684-1221

www.amstat.org

Address Changes

Amstat News Advertising