AP Statistics: Passion, Paradox, and Pressure

The Off-Diagonal Paradox: Do We Turn On More than We Turn Off?

With the evidence of the non-emptiness of both A and AC, a scientific assessment of the overall effectiveness of any program such as AP statistics then must ask, minimally, has the program attracted more students to statistics than if it were not in place? This is squarely a causal inference question, one that is arguably as hard as—and therefore needs to be addressed as carefully as—“does smoking cause lung cancer?” Counterfactual causal questions as such are often impossible to answer definitely, but nevertheless they are essential for formulating relevant comparisons, designing meaningful studies, and guarding against what I called incentive bias (Meng, 2009), that is, humans’ tendency, however subconsciously, of selectively collecting and presenting evidence that support one’s causes. Minimally, it reminds us that given that the general demand for statistics has been increasing rather dramatically, especially in recent years, any type of increase in enrollments over the years itself cannot be taken as scientific evidence of the effectiveness of a particular program intended to attract students to statistics.

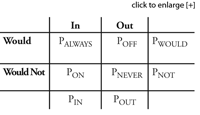

To see this clearly, let us use a generic binary “in” and “out” variable; here “in” can mean to take a statistical course or to major in statistics, or some other outcome. Regardless of its actual meaning, Table 1 is applicable to any program designed to attract membership.

Here PALWAYS and PNEVER are respectively the percentages of students (at time t) who will enter and not enter statistics regardless of whether our program is in place or not; POFF is the percentage of students who would enter statistics but got turned off by the program, and PON is the percentage of students who would not enter statistics but got turned on by the program. From this setup, conceptually it is clear that observing PIN = PALWAYS + PON , or even directly observing PON, large or even increase over time, says little about the overall effectiveness of the program because POFF can also be large and even increase over time, which can offset the gain by PON whenever POFF > PON.

This, of course, is trivial arithmetic. But just as Simpson’s paradox can be explained by trivial arithmetic, yet has led to numerous erroneous conclusions throughout the history of quantitative investigations, it is easy for us to focus on the “In” column because it is the population most easy to identify and sample from (as in RPFHS), and arrive at assertions of the benefit of the program while it actually might be doing harm in reality. To raise awareness of this phenomenon, I suggest it be recognized as the “Off-Diagonal Paradox”, invoking a similar connotation of “paradox” as in Simpson’s paradox to urge investigators to always keep in mind the need for comparing the two cells along the off-diagonal in Table 1. The word “off” should also serve as a reminder that the effectiveness of the overall program for recruitment cannot be assessed by only asking those who are already in: we need also to ask those who are off or out.

For AP statistics, the inequality POFF > PON can hold even when PON increases as long as POUT remains large (which is true, for example, for majoring in statistics), and when there are more poorly taught AP courses than well taught ones; the latter is one of the issues needing to be examined in any assessment of the overall impact of the AP program. Not having enough well-qualified teachers is a well-known problem, even at the college level, a situation summarized so vividly by a college professor who wrote to me: