State of the Workforce Data Infrastructure

Experts Express Concern for Future Relevance of Bureau of Labor Statistics

Steve Pierson, ASA Director of Science Policy

In the latest feature examining the state of the US data infrastructure, the Count on Stats team spoke with three experts on the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Katharine Abraham was BLS commissioner from 1993–2001, and Erica Groshen was BLS commissioner from 2013–2017. Ken Poole is the chief executive officer of the Center for Regional Economic Competitiveness and longtime and widely recognized leader in the BLS data user community.

BLS is the principal federal statistical agency measuring labor market activity, working conditions, price changes, and productivity in our nation’s economy. Established in 1884 as the Bureau of Labor in the Department of Interior, and after 15 years as an independent department starting in 1888, it was incorporated into the Department of Commerce and Labor in 1903. Ten years later, it was transferred into its current host agency, the Department of Labor, upon the department’s creation.

The second-largest federal statistical agency by budget, the BLS is also among the few such agencies with the highest stature and strongest autonomy. It is one of only two of the 13 principal federal statistical agencies reporting to the office of the host agency head and one of only three whose leader is presidentially appointed and senate confirmed—for a fixed term, rather than serving at the pleasure of the president. BLS also has strong control over its budget—once determined by the administration and congress—and publications. For information technology (IT), there is no interference with such operations to collect, process, and disseminate statistical information, though there has been repeated interest in incorporating BLS IT into the Department of Labor.

Despite such strengths, the experts interviewed here express deep concern about the challenges the agency faces to meet data user demands for real-time, granular data amidst growing competition from private sector data providers.

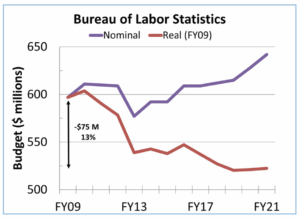

Among the BLS’s biggest challenges over the past decade has been budget cuts leading to loss of purchasing power. During the federal budget sequestration years starting in 2013—the year Groshen was confirmed as commissioner—the BLS budget was cut in real dollar terms. While restored in nominal dollar terms by 2016, the BLS continued to lose purchasing power, cumulating to a $75 million loss (13 percent) since FY09, as shown in Figure 1. Abraham, Groshen, and Poole speak to the effects of these cuts in their responses below.

Coordinating and sharing data with the other two federal economic statistical agencies—the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) and the US Census Bureau, both in the Department of Commerce—is another major challenge for the BLS. Being distinct agencies in different departments, these three agencies experience significant legal and bureaucratic hurdles to data sharing and coordination, hurdles that ultimately increase respondent burden and result in discrepancies between agency releases.

The current administration, as well as the prior two, have attempted to enhance data sharing for the three economic statistical agencies. In the early 2010s, the Obama administration launched a “data synchronization” effort, a revenue-neutral proposal to enable the BLS and US Census Bureau to better synchronize their business lists and broaden BEA’s access to Internal Revenue Service (IRS) business tax data. Unfortunately, this initiative failed to gain momentum in Congress. The same is true of a Trump administration proposal—part of a larger government streamlining initiative—to reorganize BLS, BEA, and the Census Bureau under the Department of Commerce “to increase cost-effectiveness and improve data quality while simultaneously reducing respondent burden on businesses and the public.” The Biden administration, in their FY22 budget request for the Department of Treasury, proposes to provide BLS and BEA expanded access to some federal tax information. Congress so far has not acted upon this proposal in their FY22 appropriations bills.

While concerned about the many challenges the agency faces, the BLS experts also praised the current BLS leadership, the agency’s nimbleness during the pandemic, and the progress BLS has made over the last few decades to better meet data-user needs.

The bottom line is that, despite having a high degree of autonomy and stature, the BLS is hampered in its efforts to track the rapid changes in the economy as well as it would like; meet data-user demands for more timely, granular data; and address declining response rates. Its future relevance may be at stake. Nonetheless, BLS continues to produce widely respected and monitored gold-standard data on employment, working conditions, productivity, and inflation.

BLS is best known for its monthly employment reports. What are the bureau’s next two highest-profile programs? What program do you wish were better known?

Katharine Abraham

Right now, lots of people are paying attention to inflation, so the Consumer Price Index is in the spotlight. Because of the ongoing discussion about how difficult employers are finding it to recruit people, the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) data also are getting a lot of scrutiny.

Erica Groshen

I agree with those two and note that high-profile depends on current events and audience. Financial markets always look at the Consumer Price Index, while others’ attention waxes and wanes. On BLS’s website, the part with the highest usage is the Occupational Outlook Handbook, which provides career guidance on hundreds of occupations. That’s a different audience than we normally think about for BLS, but it’s a big one and speaks to whether we have a mismatch in skilled occupations. And we cannot forget BLS’s productivity measures. While these releases don’t generate many headlines, they are truly fundamental because they drive key conversations and decisions about policy and the well-being of the country.

Ken Poole

I’d like to turn to what BLS could be better known for and, specifically, the broad interest in localizing BLS’s products on employment, productivity, inflation, and more. For unemployment statistics, prior to the pandemic, people weren’t paying as much attention to the BLS data because the unemployment rate was low and wasn’t changing much. The pandemic brought a dramatic change. Not only did people want more timely and readily available data, but they also wanted employment data that was more granularized to their communities—whether geographic or demographic.

This interest also applies to productivity and pricing data. I’m involved with groups trying to figure out the impact of automation on productivity. Automation also, of course, has ramifications for employment projections, which brings us back to the Occupational Outlook Handbook—a data source that relies on reliable projections.

More localized products from BLS would not only satisfy data-user needs, but they would also be a huge boon to economic development and job creation in communities across the US. I think it’s really important for us to use the current opportunity to help promote innovation and reinforce the innovation that’s been going on.

What are the biggest challenges facing BLS?

Ken Poole

Relevance. With demand for data way up and private sector providers in the marketplace providing more timely and responsive data, BLS is increasingly not being seen as the primary source. That’s not to say the data available from those other sources is more accurate or valuable by any stretch of the imagination. But I think that’s the biggest challenge—how do you balance the need for being the gold standard for data with the marketplace demands for immediately available data to drive decisions?

For example, ADP gets its employment data out before the BLS employment outlook to influence markets and give its customers advance warning about government reports. There’s also the job openings and closing data that Burning Glass puts out. These private vendors are becoming direct competitors with BLS as a go-to source for data. While we can argue over the relative reliability of what these vendors produce, those entities are gaining visibility because they’re getting data out there quickly. It’s affecting the BLS brand.

People love JOLTS, for example, but the problem in my community is that it’s experimental at a state level. We really need it at a labor market–area level. The BLS employment projections program is done at a national level; we’re reliant on Employment & Training Administration (ETA) funding to support the production of substate-level information, and those projections are not done consistently across the states. In the current environment, policymakers want and expect real-time, localized data. They view BLS as the historian of data. Even the most current disaggregated data being released from BLS is three or six months old. Well, look at how quickly that pandemic hit us and how differently it affected various groups. These kinds of challenges are going to continue to affect how people perceive BLS and the value of BLS.

Katharine Abraham

This is a challenge not just for BLS but for all the statistical agencies. They’re no longer the only entities collecting and disseminating data. But the existence of labor market data from other sources doesn’t make the BLS data any less relevant. One of the first things ADP, Burning Glass, or any of the other private sources of labor market data will mention when they talk about their data is that they are confident in their numbers because they track the BLS numbers. There is definitely a role for the gold standard data.

That being said, all the statistical agencies need to be thinking about what their role is. In my view, it’s not necessarily just producing the official statistics we all know and love. Yes, there’s a concern that, if a statistical agency puts out products that are timelier or more disaggregated but based on incomplete data, it might undermine the brand. I am confident, though, that there’s a way to differentiate between the official statistics that are the gold standard and more experimental measures that the agency has produced because they meet a need for more timely or more granular information.

Erica Groshen

I agree. We need to figure out the best relationship between the gold-standard series (where consistency is really important) and more timely and relevant data that addresses the particulars of current situations. This could involve a sunset provision for the data programs, so people know BLS will not be asking these questions forever. Having the capacity to ask the new questions quickly, with no expectation that you will ask them forever, is important. Related to that is the challenge of incorporating new data sources into the existing programs without undermining their quality or consistency, or having to change sourcing every week.

Some internal challenges, besides funding constraints, include attracting and retaining top staff in an age when data science is so important. In the long run, it should help the statistical agencies to have more inflow and outflow of people between the private sector and public sector. However, this is a challenge for the agencies in the short run because of the current high demand for data science skills outside of government. Unless the agencies can better align compensation with the external market, this will be a problem in the long run, as well.

Another challenge is achieving the economies of scale and scope in operations to get the biggest bang for everyone’s tax dollars while preserving independence. Since the passage of legislation in 2015, the statistical agencies are being required to try to achieve such efficiencies (by sharing computer systems, human resources, travel, and other such functions) within parent agencies instead of with other statistical agencies. This path risks undermining the independence of the agency and may not generate savings. Many needs of the statistical agencies are quite different from those of other parts of their parent agencies. Having the parent agency leadership (with their policy and political focus) in charge of shared services puts the statistical agencies in a potentially compromised situation. Whereas if you shared services among statistical agencies, you’d have more commonality of mission and roles and could avoid the potential for political interference.

What has been the cost of the 13 percent loss of purchasing power over the last 12 years to the US economy and labor?

Erica Groshen

Early in my term, because of budget cuts, I had to eliminate the mass layoff statistics, the green jobs initiative, and international labor comparisons. Part of the reason for choosing these programs was that they were underfunded, so they weren’t what they should have been to begin with. But the needs that sparked their creation are still out there. With more funding, BLS could have conducted the programs the right way. In another example, JOLTS was started on a bit of a shoestring, so the sample size was not as big as it should have been. Even with the limited sample, the program has proved quite valuable.

BLS has put forth initiatives to improve its timeliness and granularity, but these have not been funded. BLS has also been trying to modernize its Survey of Consumer Expenditures for two decades now—at a snail’s pace because it has had to do so without additional funding. In one more example of “deferred maintenance,” I think we all agree it’s time to rethink how we do the occupational projections.

The overall point is that statistical programs need the bandwidth to do two things in addition to producing their regular releases. They must always be testing and validating improvements to meet data users’ needs and keep pace with technological and economic changes. And they must have resources to provide resilience in case of potential disruptions such as weather events, strikes, pandemics, and so on. The loss of purchasing power has limited BLS’s ability to innovate as much as they want to and narrowed their margins for resilience. So, the budget hit has been costly in terms of timeliness, frequency, granularity, agility, and relevance.

Katharine Abraham

A lot of what resource constraints do is lead to scrimping on the infrastructure—for example, not updating the computer systems, not giving your staff the appropriate training, or not funding the states at the level they need to do the work on the federal-state cooperative data programs.

Unfortunately, that can translate into negative effects on the quality of the data. The deterioration in data quality may not be very visible, and if the agency continues to produce the data products, users may not notice, especially not right away. But I really worry about the long-term impacts of this on the quality of the data.

The increasing difficulty of collecting survey responses continues to be a big issue. I have been shocked by the magnitude of the increase in nonresponse in recent years. Even for the agencies’ flagship surveys, it’s getting harder and harder to collect survey data. The Current Population Survey response rate, for example, has fallen by roughly 10 percentage points in the last 10 years. We need to rethink how we’re obtaining the information needed to produce the statistical data series users rely upon.

Ken Poole

Over the past two decades, BLS has endured a period in which annual budgets were steady or received slight cuts. Year after year, we heralded these as small wins in an environment in which many other federal labor department programs were enduring massive budget cuts. However, we continued to operate so the public did not see the degradation in resources available. As a result, the impact of these decisions were not clear to the public. Sometimes you have to cut the services to get attention to the impact of these thousands of decisions over the years.

These cuts have been a particular concern to the state labor market information agencies. They have endured sizable budget cuts, not only from BLS but also from ETA—their two primary sources of income. So, some states are reallocating dollars from the general state fund to make up for the federal funding shortfall, while other states simply don’t have the resources to staff the data gathering and cleaning programs they once had. In some cases, the state labor market information agencies are basically hustling business from other state agencies to keep their staff in place because they don’t have the resources, which may not be how we want to run our statistical agencies charged with providing public data. That means those states are focusing on doing whatever the immediate project is, as opposed to making sure we all have the high-quality, well-maintained data we need over a period of time.

BLS’s occupational projections data is a great example of how ETA had to step forward to ensure state data remained available when BLS cut programs in the past. State and local projections must wait until BLS releases national projections before the state agencies can even begin their work. As a result, the data is often out of date by the time it comes out. In addition, due to cost constraints, survey data is limited so emerging occupations are lumped within existing occupations far longer than might otherwise be necessary. It also takes years until emerging occupations show up in our data.

The perfect example is data scientists. How long did it take us to get data scientists into the occupational system? Think about cyber networks and cyber security issues. Where do you find cyber information security specialists, and how can we bubble up these and other rapidly changing occupations more quickly? We need to invest in our understanding of the rapid changes to our occupational framework, and maybe this notion of skills taxonomy will help us see these changes more rapidly. The Occupational Outlook Handbook is the most widely read document on the BLS website and it relies on BLS occupations survey data, so it is the most significant resource BLS provides to the general public. That means occupation data guiding students toward new careers needs to reflect those emerging new opportunities.

Declining response rates and small sample sizes sound like technical issues data collectors must address, but they affect data relevance. We need to connect these issues in the minds of policymakers to the similar problems that face opinion polling that electoral candidates experienced in the last couple of elections. We can’t assume we’re getting to the people we’re supposed to be getting to. That’s why we worry about the quality of polls and why we should also worry about the quality of survey data about labor markets. If we can begin to connect that dot between this issue and the value of administrative data sharing as an alternative to surveys while also ensuring more transparency and better governance of data sharing across the statistical agencies, we might have a lever to help us overcome legal and policy barriers to the effective use of administrative records.

How would you broadly assess the state of BLS?

Erica Groshen

BLS continues to function well. Yet, serious impediments prevent the agency from doing many things to further improve its products. Besides funding, there are the very real threats to BLS autonomy I already mentioned. Further, their coordination with their sister economic statistical agencies, the US Census Bureau and BEA, is limited. Federal law prohibits the Census Bureau from sharing business information based on IRS data. So, the agencies’ sampling frames are different and they get different results for the same concept, such as industry employment. They also have different approaches to aggregating industries and occupations and use different geographic areas. Such inconsistencies make it difficult to combine data produced by the three agencies. Lowering the barriers to coordination among these agencies would address this. It would also facilitate more reuse of data, which would ease the burden on data suppliers and the modernization efforts.

Katharine Abraham

Building on Erica’s point, the best path forward may actually be to combine BLS with the BEA and the economic statistics part of the Census Bureau. In the past, I have resisted this idea. Any kind of reorganization in government is disruptive, and I did not believe the benefits would be worth the cost. But I’ve come around to thinking that, in this new world where we increasingly want the agencies to be making use of new types of data to do new things, it is unlikely to be efficient to have the agencies all pursuing those goals independently. Rather than the BLS, the BEA, and the Census Bureau each contacting the same potential sources of useful economic data, for example, a combined agency could approach those sources on behalf of the statistical system as a whole. You obviously would need legislation to create a new combined agency. Perhaps you could get to the same place with better coordination among the separate agencies, but I’m skeptical.

Erica Groshen

I agree. In order to do that, you need an empowered person or entity over all three agencies. It would make a lot of sense to have the chief statistician of the US take on this role. The chief statistician would oversee some key federal statistical agencies, rather than leading only a small staff in the Office of Management and Budget. Furthermore, you would want this combined agency to have clear independence, that is, not to report to a Cabinet secretary.

Ken Poole

I’m going to play devil’s advocate. One of my biggest concerns in the way the agencies currently operate and may very well be exacerbated in a situation where the agencies are together is that they seem to be somewhat divorced from who their client base is. BLS has historically been primarily oriented toward OMB or Congress and toward the need for national data that contributes to the principal federal economic indicators, but one of the key reasons why statistical agencies are successful in getting resources and innovating is that they respond effectively to a broad customer base.

Often innovative data programs come from program offices, rather than the statistical agencies, because they are responding to immediate customer needs. For example, one of the biggest innovations in employment-related data provision is the Occupational Information Network (O*NET). It’s operated out of ETA, rather than BLS, even though ETA still respects BLS as the primary source for methodology and methodological improvements. O*NET is driven by the ETA customer base—workforce agencies, education partners, or economic development agencies.

So, this tension exists between what the statisticians or technocrats in charge of the statistical agencies think innovation is needed and what their customer base desires. However, the customer base has Congress’s ear. So, if we were to go to a model in which the federal economic statistics were aggregated into one place, opportunities for the customer’s voice to be heard would need to be robust and transparent.

I think this disconnect is part of the struggle the statistical system has had over the last two decades, where the statistical system has been fighting over budget scraps when we had this push and pull of different policy priorities. So, I think there’s something to be said here for how we engage the customer in this process in a way that helps the agencies become as responsive as possible within their budget constraints. The challenge is that these customer demands don’t occur in many conversations about statistics. Instead, they occur in the natural ebb and flow within program agencies about policy priorities. This engagement with program agencies will need to balance the need for independence in the political environment that we’re talking about with the need for maintaining relevance for the statistical agencies.

This disconnect is also the reason I would describe BLS as at risk. They don’t have the depth of customer base many other programs have. Congress and the administration, for example, are deliberating a major investment in infrastructure and nobody seems to be buying the argument about data being a core infrastructure. I think that’s because BLS just doesn’t have the community-based advocacy network it needs to make a big difference on Capitol Hill.

Katharine Abraham

Speaking to the advocacy network, the Friends of BLS is a great innovation. It’s always been hard to generate support for the BLS that translates into advocacy. When I was at the BLS, we used to talk about the support for BLS being a mile wide and an inch deep. There are a lot of people who appreciate BLS data, but the BLS is hardly anyone’s top priority.

On a positive note, BLS benefits from good leadership. Commissioner Beach is focused on the right issues and doing a really good job in his efforts to move the agency forward.

Ken Poole

I agree with you. I’ve been monitoring BLS from the user-community perspective for more than two decades and I have seen an evolution in how I interact with BLS and how BLS interacts with the broader community. I think there have been really important shifts in the culture of BLS’s leadership to be more responsive to economic and societal dynamics. BLS also seems to be shifting from being perceived as a survey agency to more of a data aggregation, collection, synthesis, and interpretation agency. I think this is a healthy move despite the political risks of such innovation. To reiterate my point about relevance, I don’t think BLS can remain relevant unless it makes these kinds of changes.

If BLS were provided unlimited resources, what would you like to see the agency do first?

Katharine Abraham

The quality of the national data the BLS produces obviously is important, but I also would urge the BLS to expand its efforts to produce more granular data on a timelier basis. What is the saying? All politics is local? Several years ago, I served on a panel convened to evaluate the Census Bureau’s program of annual economic surveys. We brought in a group of state and local officials to talk about the economic data produced by the Census Bureau. Like the BLS, the Census Bureau produces a fair amount of state-level data. But what these local officials really wanted was data for their metropolitan area or their county or, even better, even more disaggregated geographies that they could aggregate up to geographies that were meaningful to them. And they wanted data that was current, not data that refers to what happened a year or two ago in some cases. We are just so far from being able to meet this demand.

Erica Groshen

The national needs are important. We don’t want to jeopardize the quality of the national statistics, but I think there’s a huge demand for not just state, but local area, data. With all this private sector information—the ADP data, Burning Glass data—if BLS worked with some of those private sector vendors and figured out ways to produce modeled statistics that took that data as input, it would be possible to produce really valuable information that’s not being produced now. It would be a huge investment required to do that.

And so let me take it one step further. I would give BLS ongoing access to enhanced unemployment insurance (UI) wage and claims records, with occupation, hours, location, and demographics added. These are the recommendations of the Workforce Information Advisory Council’s (WIAC) 2018 report. Implementing this will allow BLS to do everything we’re talking about. Such an effort would complement a business-led effort to create standardized employment records in companies. Funding the states to curate them appropriately and aggregating this data would be immensely powerful, yielding true economic statistics (such as improved mass layoff statistics) based on the wage and claims records at a more granular level than we have seen before. With modeling, one could also address the timeliness issue. And BLS would be able to eliminate or reduce the scope of at least two of its current surveys.

Ken Poole

I completely agree with Erica that BLS having access to enhanced UI wage record access would address many of the BLS challenges. We’d also be learning a lesson from the private sector, which models existing data to deal with privacy and confidentiality issues and create projections that give them a better sense of what’s happened recently, what’s happening now, or what’s likely to happen in the not-too-distant future—all in a much more seamless way. Currently, the way the system is set up, it takes so much time to do that kind of data alignment, that it’s not worth using public data. So, the user gives up on federal data and basically says that to actually use data in a way that is most relevant, they must go through a private intermediary to do so.

I also don’t want to lose the idea of increased sharing of business lists between the Census Bureau and BLS already mentioned, because one of the most frustrating things for the user community is for one data source to tell us there are 300,000 manufacturers in the US and another data source to say 400,000. They’re both reliable federal statistical agencies saying different things. And it’s because they can’t share their data to align their answers. It creates unnecessary confusion, and that shouldn’t be the user’s problem. We should figure out a way to solve that problem among the statistical agencies.

O*NET really needs to be upgraded to be structured and standardized. Operated out of the ETA, it’s essentially a survey of jobs and the skills required to do those jobs. It isn’t a BLS product, but it ought to be because it’s one of the most powerful tools we use in this day and age and because it digs down beyond counting numbers of jobs and into the makeup of those jobs. This is related to a BLS initiative underway to design skills taxonomy, because we’re beginning to track and ask questions about skills more so than about industries or occupations in terms of worker preparation.

In short, BLS needs to develop data on skills, and I’ll reiterate the need for localized, real-time, high-frequency, forward-looking labor market information.

The idea of BLS making more use of private sector data has been a strong theme in this discussion. How feasible is this?

Erica Groshen

There are a lot of issues along that path. Will those organizations charge the statistical agencies for the data? Will the data continue to be available? Will quality be maintained? Will companies use pre-release information to front-run statistical releases? Who is responsible for privacy? These are resolvable, but it will be easier to do so if the agencies can approach the private entities as a united front.

Ken Poole

Several other agencies are out there buying this data, independent of the statistical agencies, without understanding how it might relate to the public statistics. You don’t have the expert opinion, or you’re paying for additional expert opinion, to figure out how their stuff is applicable in the various circumstances. There is something to be said for the statistical agencies using it to help model their data. Even if it does cost money, it would be better for BLS to buy it once than to pay for it 1,000 times through the various other federally funded programs.

Readers of this discussion may infer the private sector may one day supplant the need for some of BLS’s programs. Is this realistic?

Katharine Abraham

At least with respect to the core BLS data products, that’s not realistic. There will continue to be a need for publicly available economic statistics that everyone agrees are gold standard measurements. Even with regard to more detailed and more real-time data, statistical agencies like the BLS are likely to have an edge when it comes to producing statistics that are broadly representative. While information from private sources certainly can supplement the official statistics produced by the BLS and other statistical agencies, I don’t see that information ever supplanting the official statistics.