What Is Statistics?

Mary J. Kwasny, Northwestern University; Michael J. Anderson, StressBusters; and Jesse Miller, University of Minnesota

At one point this summer, the Statistical Consulting Section forum on ASA Connect held an interesting discussion about where to categorize statistics. Essentially, the question was:

After several opinions were brought forward, some of us thought an article summarizing the discussion would be interesting for Amstat News readers. You may have heard that if you ask two different statisticians, you’re likely to get two different answers. It is not much of a surprise that my coauthors held two distinct conclusions after reading the same discussion posts. Some of the arguments focused on schooling—what is taught and where it is taught. Other arguments focused on the goal of the discipline. As such, we present the following two conclusions to consider.

Conclusion 1: Statistics Is One of the Branches of Mathematics

According to the American Mathematical Society, to classify its branches of mathematics, they use the MSC2020-Mathematics Subject Classification System. This includes classification number 60—probability theory and stochastic processes—and 62—statistics. Indeed, most Google searches from Britannica to Wikipedia list statistics as a branch of mathematics.

As the field of statistics grew, many key mathematicians were responsible for its foundations. [Jacob] Bernoulli, [George] Boole, [Augustin-Louis] Cauchy, [Ronald] Fisher, [Joseph] Fourier, [Carl Friedrich] Gauss, [Joseph Louis] Lagrange, [Adrien-Marie] Legendre, [Abraham] de Moivre, [Siméon Denis] Poisson, [John] Venn, and [Waloddi] Weibull all contributed to probability and statistics via laws, inequalities, distributions, and estimation methods. If statistics is not a branch of mathematics, why is it that so many mathematicians are responsible for the bulk of its foundations?

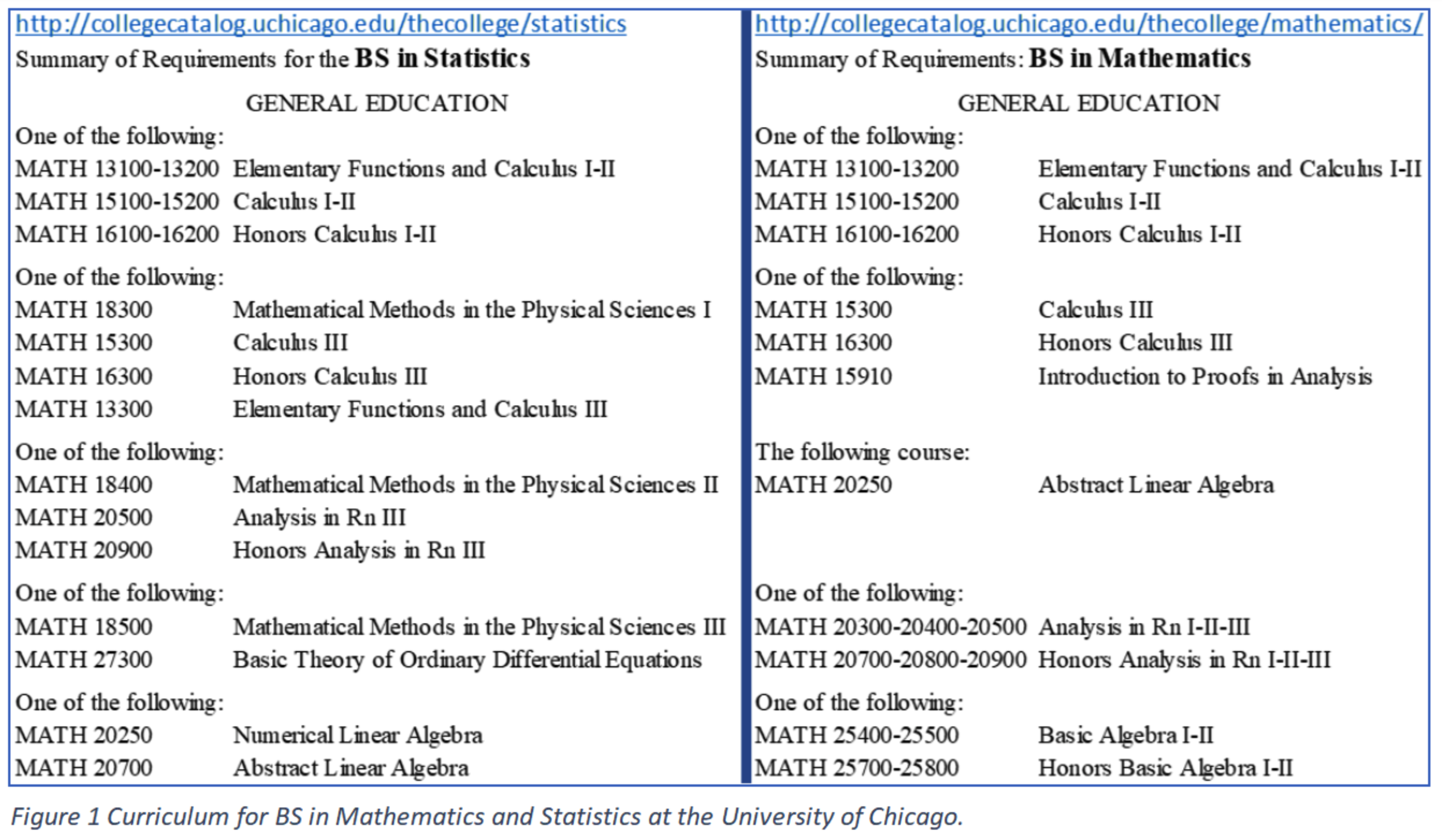

The curriculum for bachelor’s degrees in mathematics and statistics is typically similar at most institutions. At The University of Chicago, there is little difference between the statistics and mathematics majors; this can be expected since they are both mathematical disciplines.

Just one of dozens of theories that required proving in a typical mathematical statistics course—required in most MS in statistics programs—is the Cramer-Rao inequality.

This type of mathematical rigor would be required only of those degrees that fall within the math category (i.e., one of the branches of mathematics).

Finally, one need only to thumb through an issue of JASA to clearly see that statistics is, indeed, one of the branches of mathematics.

Conclusion 2: Statistics Is a Science

To define a field of study, it is necessary to define not only the subject (e.g., physics concerns itself with certain aspects of nature), but also the means by which the field approaches that subject (e.g., physics uses the scientific method). Without this distinction, it is difficult to clarify the difference between physics and mythology, for example, as both deal with the nature of the universe. Note that the terms “field,” “subject,” etc. are often used synonymously, but the use here refers to distinct things.

A working definition of mathematics is that it concerns itself with measurement per se and generalizations thereof. The means by which it does so is a combination of logic and intuition. The logic part is easy to see. The intuition part is specifically an implicit appeal to the reasonableness of the assumptions (e.g., the selection of axioms) and a general agreement that anything left logically vague in the proof could, in principle, be expressed as a formal logical proof using basic assumptions and methods of inference.

This is in direct contrast to a scientific proof, which is empirical by nature. There is no proof in science that does not ultimately rely on an appeal to what is observed. The mathematical proofs of theoretical physics are “mathematical” in that they make extensive use of mathematics, not because the result is known to be true in the universe once the mathematics have been shown to be correct. Truth here is approached by an appeal to observation. Mathematical proofs have no such appeal.

To which of these is a statistical “proof” more similar? I contend that such a proof is entirely scientific in nature. A statistical proof is a proof about something in the world and cannot be complete without a comparison to the phenomenon under consideration. Mathematics must be used in this process, but that makes the proof no more mathematical than it would a proof in physics. We must distinguish between the use of mathematics in a field and the field of mathematics, itself. Note that this does not refer to a proof of a mathematical result, such as the Central Limit Theorem, used in statistics. Such a proof is clearly mathematical in nature.

By the definition given above, statistics is not a subfield of mathematics. Statistics, like physics, uses measurement extensively, and therefore the use of mathematics is similarly extensive. That does not make statistics a subfield of mathematics, though. The approach of statistics to its subject is different from the approach of mathematics: The former is a science, and the latter is not.

Can We Draw a Conclusion?

It might help to examine the etymology of the words “mathematics” and “statistics.” From etymonline.com, mathematics is “the science of quantity; the abstract science which investigates the concepts of numerical and spatial relations,” whereas statistics is the “science dealing with data about the condition of a state or community.” These definitions seem to echo the sentiment in the discussion about the goal of the field: mathematics dealing with concepts and statistics dealing with conditions of the state.

I believe we all agree statistics is not “abstract,” and mathematics courses apart from probability or statistics rarely involve a data set. Several institutions offer mathematics degrees with a minor or concentration in statistics, but not a minor or concentration in algebra or geometry, inarguable branches of mathematics. So, perhaps there is something a bit more going on with statistics than other subdisciplines.

Clearly, there are valid points made by both perspectives. We leave the decision to you. However, we do advise you to stay away from non sequiturs such as “Statistics has ‘missing data,’ but mathematics has ‘imaginary numbers.”

Visit this discussion under the ASA Statistical Consulting Section on the ASA Community site or after reading this article, go to ASA’s Facebook page and cast your vote as to whether statistics is a branch of mathematics.

Energetics is part of a broader field of chemistry called thermodynamics or thermochemistry. It is all about the energy changes that happen in a chemical reaction. In other words, it’s the study of the flow of energy in chemical reactions. Because it seeks knowledge, I’d say it’s a science (“science” is derived from the Latin “scire,” “to know”).

By way of analogy, to me as a Bayesian, statistics is all about the probability changes that happen in the presence of new data. In other words, it’s the study of the flow of probability in response to observations. A priori, an unknown quantity had a probability distribution; having observed new data, the statistical question is, then, how does that distribution change in accordance with mathematical laws? To me, statistics is, therefore, a science, by the same reasoning I think energetics is a science.

Frequentists would not like that conception of statistics, though, since to them, probabilities cannot apply to parameters.