The United States Needs to Fill the Gaps in Its Crime Statistics

Editor’s Note

Janet L. Lauritsen is Curators’ Distinguished Professor Emerita in the department of criminology and criminal justice at the University of Missouri – St. Louis and 2022 president of the American Society of Criminology. She also served as chair of the Panel on Modernizing the Nation’s Crime Statistics for the National Academies’ Committee on National Statistics and the ASA Committee on Law and Justice Statistics.

The comments here are adapted from Lauritsen’s 2022 presidential address to the American Society of Criminology published in Criminology in 2023 and presented at the March meeting of the Council of Professional Associations on Federal Statistics.

The US lacks sufficient data for many types of crime of great concern to society, and this is particularly the case for crimes falling under federal—as opposed to state and local law enforcement—jurisdiction. This lack of data poses significant problems for determining whether government resources are adequate for responding to these crimes and whether programmatic, legislative, or target-hardening efforts to prevent or reduce their occurrence are effective.

Four-level classification with 11 first-level offense categories:

- Act leading to death or intending to cause death

- Acts causing harm or intending to cause harm to the person

- Injurious acts of a sexual nature

- Acts of violence or threatened violence against a person that involve property

- Acts against property only

- Acts involving controlled substances

- Acts involving fraud, deception, or corruption

- Acts against public order and authority

- Acts against public safety and national security

- Acts against the natural environment or against animals

- Other criminal acts not elsewhere identified

At this point, the crime data we do have is primarily focused on personal violence and property crime, often referred to by criminologists as “index” or “street” crimes, which include homicide, rape and sexual assault, aggravated assault, robbery, burglary, motor vehicle theft, and personal thefts. However, for many other types of crime, we are unable to answer basic questions about the levels and trends in the frequency with which they occur.

Consider for example, trends in financial law violations, fraud against government agencies, and embezzlements and pilferage against businesses. It is challenging to find estimates of these crimes and, when one appears to have done so, they will often find competing estimates, including some released by private groups. The amount of economic harm resulting from these types of theft crimes compared to the losses associated with the larcenies, robberies, and burglaries we do measure relatively well is challenging to assess. It is also difficult to know the level and rate of increase or decrease in crimes such as environmental law violations by businesses or persons and consumer financial and product/services fraud.

These types of data gaps are a problem not only for researchers who claim to specialize in knowledge about crime, but also for those who must respond to crime. I am routinely contacted by the media and others asking how often a particular crime occurs and whether it is increasing or decreasing, and I often find myself saying, “We don’t know” or “I am not aware of any data that can answer that question.” The people I speak with who would like to be well informed about crime wonder how this can be possible in an era that seems to be awash in data.

The modernization of US crime data is critical for providing an empirically sound and more complete description of the nature, distribution, and extent of different forms of crime; who is most affected and victimized by these crimes; and the extent of harm resulting from these incidents to both persons and society at large.

These general points were made in two reports released by the Committee on National Statistics Panel on Modernizing the Nation’s Crime Statistics. This project was prompted by the Office of Management and Budget in partnership with the FBI and Bureau of Justice, and the panel’s work involved an interdisciplinary group of scholars, practitioners, and stakeholders. The panel’s first report recommended a new classification system for crime, and the second report suggested methodological and implementation strategies for collecting data based on the recommended crime classification. These efforts constituted the first major reassessment of the definition and coverage of US crime statistics since the Uniform Crime Reporting program was developed in 1929. The reports contain a wealth of information about the crime classification system, as well as recommendations and suggestions for how this work might move forward.

Of the 11 major categories of the panel’s recommended crime classification, the first five major categories include violent and theft offenses that currently have the greatest degree of coverage in the nation’s two major crime data sources. Data coverage for the remaining categories is woefully sparse and incomplete. These offenses include acts involving controlled substances, fraud, deception, corruption, public safety, and national security, as well as acts against the public order, environment and animals, and other offenses. The details of these categories are elaborated upon in the panel’s first report and in my 2022 presidential address to the American Society of Criminology.

Finding and developing the data necessary to understand the full range of crime will not be easy. Many forms of crime will be more difficult to enumerate than the traditional index crimes, and simple counts of incidents may be misleading or uninformative. For example, a single ransomware attack might hobble the personal computer of one victim, or it might shut down the operations of an entire hospital, school, business, or municipality resulting in many more victims and more extensive damage and costs. The development of reliable new metrics will be necessary for the system of crime data collection methodologies that was recommended by the Committee on National Statistics panel.

New resources will be necessary to mount, coordinate, and govern these efforts, as well as to assess the quality and usefulness of the new and more detailed crime data. The criminology field must pay greater attention to the development of data that forms the basis of their research if they want their work to continue to benefit both scholarly and public interest.

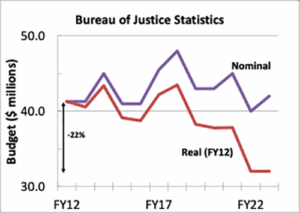

I am heartened to see the major initiatives of this administration to provide more robust data on crime and our criminal justice system. The Bureau of Justice Statistics has been chronically under-resourced for the demands placed on it, and thus it is imperative it receive the necessary federal resources proposed in this year’s budget and beyond to do this work.It is also critical for the executive branch of the federal government to be committed to providing the coordination to develop the data necessary for setting priorities and policymaking, particularly because so many of these crime types fall under federal jurisdiction.

Without strengthened federal resources and financial supports—as well as governance for crime statistics that operates under the established principles and practices of a federal statistical agency—the US will continue to be plagued by incomplete crime data and an increasing set of competing so-called ‘facts’ about crime put forth by private companies with proprietary methodologies or organizations and individuals with vested financial and advocacy interests in their depictions of crime.

We must also begin to fill in the crime classification proposed in the panel’s first report with information about potential data sources for crimes not well measured. Ideally, this work would involve a Bureau of Justice Statistics ad hoc working group and criminologists, practitioners, and data holders with a wide range of knowledge about types of crime that are not well measured. The combination of knowledge from those in- and outside the statistical agency is necessary to further this progress, as it will require various forms of expertise. As information about potential data grows for each of the crime categories, a straightforward documentation of this information would serve as a major resource for academics, other researchers, journalists, policymakers, and the public.

For the safety of our communities and public servants, and to improve evidence-based policymaking, we should support efforts underway to fill the data gaps in our measures of crime and the criminal justice system.

Great article. Economists talk about the changing mix of goods and services over time. Professor Lauritsen applies this general principle to crime in an interesting way.