Statistics: Your Chance for Happiness (or Misery)

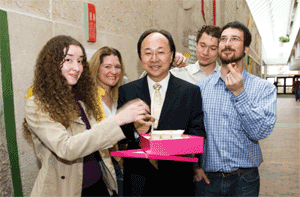

Xiao-Li Meng and his “happy team” on the opening day of Stat 105. From left: Cassandra Wolos, Kari Lock, Xiao-Li Meng, Yves Chretien, and Paul Edlefsen. Photo by Rose Lincoln/Harvard News Office

Honey, I Know You Are in Excruciating Pain, but Which Treatment Do You Want?

Here is another real-life scenario that, depending on your understanding of statistics, could literally make your happiness or misery. Two treatments for kidney stones were evaluated in a medical study. Treatment A has a success rate of 78% and treatment B a success rate of 83%. Which one should you choose? Treatment B, right? Well, what if I told you that when treatment A and treatment B are applied to those who suffer small stones, the success rates becomes 93% and 87%, respectively? And when they are applied to those who carry large stones, the success rate is 73% for treatment A and 69% for treatment B? That is, regardless of the sizes of the stones, treatment A has a higher success rate. Then you should choose treatment A, right?

Confused? You should be if you don’t understand Simpson’s Paradox (no relationship to O. J.). There is actually no paradox at all in the mathematical sense. The numbers I reported above are from an actual study from the March 29, 1986, issue of the British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed). For treatment A, there were 350 patients, 87 carrying small stones, among which treatment A was successful for 81. For the remaining 263 patients (with large stones), treatment A was successful for 192 of them. For treatment B, there were also 350 patients, with 270 suffering small stones, among which treatment B was successful for 234. For the remaining 80 (with large stones), treatment B was successful for 55.

Now, you do the math and then think statistically how this could happen. That is, how could treatment B have a better success rate overall than treatment A and yet a worse rate in each subgroup defined by the stone size? What could cause such a paradox? What are its general implications? Let’s label this Puzzle Three and read on.

The Best Thing About Being a Statistician Is That You Get to Play in Everyone’s Backyard

This line is attributed to John Tukey, a statistical giant who also coined the terms “software” and “bit.” This is literately true, as many statisticians can testify, including me. In addition to teaching Real Life Statistics and other courses, I am involved with the following:

- Conducting a workshop with researchers from the Harvard-Smithsonian Observatory on dealing with astronomical amounts of data from astrophysics

- Working with a group of geophysicists from the University of Illinois and the National Weather Service on climate change

- Writing papers with a team of psychiatrists from the Harvard Medical School and Columbia University on estimating disparities in mental health services

- Collaborating with researchers from Harvard’s engineering school on signal processing, particularly for digital cameras, via wavelets methods

- Writing articles with statistical geneticists at The University of Chicago and deCode Genetics in Iceland on how to measure information in genetic studies

- Preparing reports with my ex-postdoc at The University of Chicago on AIDS reporting delay to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Investigating statistical foundational issues such whether more data automatically imply more accurate results

If you find the range of my activities impressive, check out this site and prepare to be dazzled by the range of research my colleagues are conducting, such as Sam Kou’s pioneering work on statistical models for neon-biochemical experiments.

I hope I have provided a snapshot of how practically useful and intellectually fulfilling it is to be a statistician. I am certainly having great fun, both professionally and personally, and I hope you will be able to share some of the fun by taking at least one statistics course—no matter how much you hated the idea before. You will then easily find out the answers to the puzzles in this article, in addition to gaining many other benefits. If you want to challenge yourself, think about the puzzles now—that is part of the fun! But, if you start to lose sleep, email me at chair@stat.harvard.edu. Remember, I promised you both happiness and misery!

Great presentation of the topic, thank you! As a trainer in stats (training staff in the marketing sector, rather than students), I feel this very inspiring.