The Heart of a Statistician’s Career: Relationships and Interactions

How to be more effective in your

professional life

Doug Zahn, Consultant, Zahn & Associates

Doug Zahn taught statistics and statistical consulting at Florida State University and consulting skills in the United Kingdom Office for National Statistics. He recently won the W. J. Dixon Award for Excellence in Statistical Consulting and is currently speaking, leading workshops, and writing a book about statistical consulting that explores the concepts in this article in greater depth under the auspices of Zahn & Associates.

Our careers consist of interactions—preparing for them, having them, and carrying out the plans made during them. Some go well; some don’t. Here is an example of one that didn’t.

Our careers consist of interactions—preparing for them, having them, and carrying out the plans made during them. Some go well; some don’t. Here is an example of one that didn’t.

About 25 years ago, I managed to save just enough money to get my prized 1969 Mustang fixed and painted. At dinner the night after I got it back from the body shop, my 9-year-old son, Derek, said, “Dad, some of the MUSTANG letters on the trunk are loose.” I reacted with annoyance, saying, “No, they’re not, Derek. I just paid a lot of money to get the car fixed and painted. It’s fine!” The rest of the meal passed in silence.

A week later, I was pumping gas and discovered I was now the proud owner of a MU TANG.

Interactions always pose challenges for all parties. In this interaction, I was given relevant information and immediately dismissed it. Before reading on, I invite you to identify an interaction that did not go well in which you were a participant. Reflect on that interaction as I explore my MU TANG experience with you. I also invite you to identify a trustworthy partner with whom you can discuss your interaction.

Relationships

What does my MU TANG experience have to do with professional practice? Professional interactions involve frequent exchanges of information. This can be challenging. For example, I get exasperated when clients dismiss information I provide. Eventually, I remember the MU TANG experience and how easy it was for me to dismiss information that did not match what I expected to hear. Then, I recall once again that my job involves more than just providing information.

There are numerous other career-relevant lessons here. A key component of an interaction is the development of a healthy relationship that helps participants create an effective interaction. Though a healthy relationship is essential to the success of an interaction, rarely do we intentionally develop one.

Several attitudes and behaviors in my MU TANG experience combined in the space of a few seconds to result in my dismissing Derek’s information:

- I thought, “What can a 9-year-old know about this?”

- I was too sure I was right about my choice of body shops to check out new information.

- I got annoyed.

- I did not stay in the conversation, open to the possibility that his information could be useful.

What happened in your interaction that led it to go poorly? I encourage you to consider only your attitudes and behaviors, not those of your client.

For me, a healthy relationship includes an explicit commitment to respect the other (which includes considering his or her input), manage my emotions, and stay in the conversation. Any one of these commitments would have saved the “S.”

Interactions

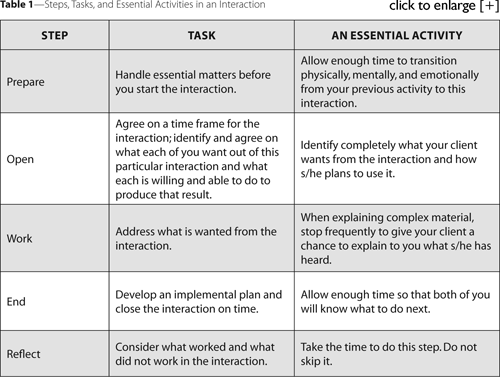

What can be done to enhance one’s career in addition to creating healthy relationships with clients? Let’s examine interactions themselves. An interaction can be broken into five steps, as detailed in Table 1.

Breakdowns

Breakdowns (failures of processes to progress or function as intended) naturally occur in interactions. An effective interaction includes the following characteristics:

- The plan developed in the interaction is implemented.

- The results of the plan stand up to scrutiny by stakeholders who were not involved in the interaction.

- Your client regards you as a valuable resource for future similar interactions.

Interim breakdowns in the MU TANG experience were my disdainful reaction to Derek’s input, my choice to ignore the input rather than explore its validity, and his choice to adopt the tenet that “discretion is the better part of valor.” Yes, staying in the conversation would have been tough for Derek; interactions that involve speaking “truth to power” are always tough. The final breakdown was the loss of the “S.”

Big breakdowns generally are preceded by smaller ones. When smaller breakdowns are not addressed, they tend to cascade until a breakdown finally occurs that is too big to be ignored.

What is useful after a breakdown occurs? Recover and learn. Before we can learn, we must first recover. Here are five steps that, in my experience, lead to recovery:

- Recognize a breakdown has occurred.

- Acknowledge your part in it.

- Pinpoint exactly what the breakdown is from the perspective of both participants.

- Identify what must be done to resolve it.

- Do it!

Perhaps the most critical activity here is acknowledging your part in the breakdown and shifting your attention from “Whose fault is this?” to “How did this happen?” This opens the door, first to recovery and then to learning.

Improvement

To improve interactions, gather data about a breakdown; analyze these data to generate possible actions or attitude shifts that may address the situation more effectively in the future; implement a new action or attitude, observing the results; assess what worked or did not work; and apply these insights to your next interaction.

Often, as with my MU TANG experience and perhaps with the one you are considering, the only data we have are memories. Much can be learned from memory data, especially if we discuss them with a partner. This is a good place to start.

However, our memories are poor recorders of the specifics of interactions, especially ones that do not go well. Video is much better and is now readily accessible, given the advent of digital cameras. What is still difficult about video is the anticipation of painful viewing. A way to manage this discomfort is to watch the video with a trusted colleague.

The coaching process is an analysis of your memory or video data. There are three aspects of an interaction to consider: interpersonal, intrapersonal, and technical.

Has a healthy relationship been explicitly created? If not, what is missing?

Were any of your attitudes, feelings, or emotions serving as barriers to effectiveness?

A useful coaching activity is to identify a breakdown you want to address. Then, look at video of the three minutes immediately preceding the breakdown for early warning signs. If you are working with memory data, discussing this time period with your partner is often useful.

For me, getting annoyed with Derek was an early warning sign that I was about to unconsciously dismiss his input, rather than consciously consider it. From this, I learned a strategy to implement: When I feel myself getting annoyed, I pause to identify the source of my vulnerability and then address it. For example, I could have suggested we check out which letters were loose.

Implementing this strategy has helped me stay in the conversation longer—a large return for the cost of a single “S”!

What’s Next?

An article can introduce ideas, but only people can implement them. What will you do with the ideas presented here? I hope you will find a partner and explore how to be more effective in your professional life. This is important, as statistical thinking has an indispensable role to play in addressing the challenges of our time.

Please email me, Doug Zahn, at zahn@stat.fsu.edu with any questions or comments you have about this article or the interaction you have been considering while reading it. Let’s talk!