What’s Our Point? Flipping the Paradigm for Communication in Statistics and Data Science

Elizabeth Mannshardt is an adjunct associate professor in the department of statistics at North Carolina State University, associate director of the US Environmental Protection Agency’s Information Access and Analytic Services Division, chair-elect of the ASA Section on Statistics and the Environment, and vice chair of the ASA Committee on Career Development.

What if we have been going about communicating the message and importance of our statistics and data science work upside down? How we talk to each other is different than how others receive and understand information, including decision-makers, policy advisers, industry leaders, the media, and the public. And yet these are often those whom we are trying to reach to engage, inform, or educate. In a global, interconnected world, science communication and shared understanding become even more essential while battling the constant pull of everyone’s time and attention. How we communicate to engage others and get our point across is crucial to our roles as data scientists.

Kathryn Sullivan—former NASA astronaut, former chief scientist at NOAA, and president and CEO of the COSI Science Center—recently spoke about the discipline of communication and framing conversation, deeming it “the new social technology” and “the most important human technology.” As data scientists, we must think beyond communicating with our scientific colleagues to effectively communicating with leaders and decision-makers, as well as the media and public. Making your point in these settings often does not fit the traditional communication paradigm found in academic research talks. Perhaps we, as statisticians and data scientists, should aim to reframe our conversations and shift that paradigm.

Let’s take a look at how we may flip the traditional paradigm for engaging in impactful and effective communication within our discipline and across scientific boundaries.

Traditional Paradigm

I was excited to be working on one of my office’s high-profile projects during my first year in government, after having transitioned from academic research. Collaborative statistical work with scientific and expert colleagues resulted in a journal paper. The paper explained a clear need for the work, gave an overview of previous methods and cleanly described new methods, and offered compelling results with descriptive graphics. It was the perfect package for communicating the message and importance of the topic—all nicely laid out in a reasonably concise 14 pages.

My boss walked into my office and said, “Give me one bullet point on this.” (What?!?!) I was a bit stunned; how could anyone possibly explain any scientific research or statistical analysis in one bullet point?

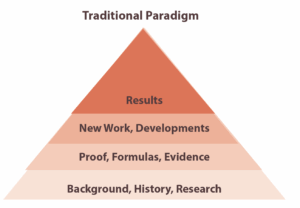

This experience was eye-opening. I, like many of us, was “raised” to read, write, and digest statistics journal articles and scientific papers under what I will call a “traditional paradigm.” In this paradigm, statisticians and scientists are often trained to present and communicate their work from the bottom up. We lay out background and previous research to set the groundwork, describe or reference theorems and formulas to offer proof, show the need for the next-step and/or novel new method, and then explain the latest work/technique/breakthrough, often including a timely application (which may have been the original driver).

There is absolutely a need for highly technical presentations, discussions, and journal articles that focus on detailed statistical methodologies. Much attention is already placed on this more traditional aspect of technical discussions and communication; it is arguably the default in conferences and colloquiums, as well as most collegiate courses. However, this traditional paradigm may miss the mark for different audiences. What is the goal for leaders and decision-makers? What is of interest to the media and the public? As data scientists engaging with these audiences, what is our point?

Flipping the Paradigm

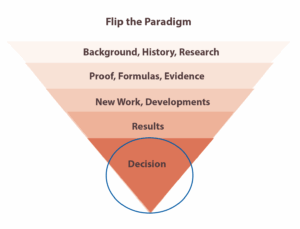

Government, academia, industry—these are different settings with varying goals and distinct considerations. Leaders may be looking to fund a new feature or product, implement or change public policy, or explore new technological innovations. The aim for conversations with the media and public may be to inform or encourage action. Across these settings, the common theme is to make a decision and spur an action. So how do we engineer effective communication for these aims?

As we walk into the room, we should lead with our point—what delivers our message and engages the audience. We should flip the paradigm with a point-first pyramid framework for presenting results and decision factors. Open with the main message, the exciting conclusion, the research findings, the decision recommendation.

Time Magazine reports you have 7–20 seconds to engage your audience. The Forbes article, “How to Pitch Anything in 15 Seconds,” describes the importance of a simple and straightforward message. In his book Language Intelligence: Lessons on Persuasion from Jesus, Shakespeare, Lincoln, and Lady Gaga, Joseph Romm speaks to the importance of having a simple repeatable “hook.” These all point to the importance of grabbing and engaging an audience’s attention. This fits into a model I aim to employ: ERI (Engage, Relate, Involve). We are not necessarily aiming to fully explain complex scientific findings in a soundbite; we are aiming to engage the audience, relate the concept to them, and involve them in the discussion and solution. If more information or technical details are wanted/needed, they are available—in your full presentation, your report, the published paper.

The need to lead with your point goes hand-in-hand with an additional key consideration: time. There is a reason they are called briefings. You may have one minute or one bullet point to get your message across—maybe less.

Last year, I was giving a briefing on a major project at my organization’s national information technology meetings. The previous session ran long and walking (virtually) into the session, I was told to keep it to 30 seconds. On the fly, I needed to condense the briefing into just my point.

Think of a colloquial elevator speech, a common technique for networking and “impressing the boss” in a short impromptu elevator ride. What excites you? What should excite them? Follow-ups may come in that instance, time permitting, or at a later point.

How We Communicate Among Ourselves

Just as important as our communication structure are the words we use. Effective communication of statistical concepts and results has become even more crucial in the age of big data / more data / better data / bad data. How do we talk to non-scientific people about statistical science in a way that can be understood and generate interest, discussion, and engagement? Being able to express the importance of our work in a way that resonates with others is critical.

Flipping the paradigm can also serve our own needs in the data science community. A statistics graduate student at a recent conference lamented they felt most presenters were giving the audience their appendix—formulas, theory, and past methods. It can be hard to follow along the entirety of complex technical details to arrive at an understanding of what is meant to be the exciting conclusion. I have often felt the same way. I remember how overwhelmed I felt at my first JSM (and since) and how I struggled through many a colloquium in graduate school and beyond. The traditional paradigm may not be the best avenue for engaging an audience that is new to the topic.

The idea of flipping the paradigm has started to spread in the scientific community, as well. Think about the last poster session you went to. What is the goal of a poster / poster session? Is it to learn everything about every project? Absorb someone’s life’s work in three minutes?

JSM 2019 had almost 900 posters—an amazing amount of information! How can we effectively and efficiently use these sessions to communicate relevant information to our current and potential colleagues?

Not only is a poster based on the traditional paradigm not designed to bring new statisticians or scientists to the conversation and research area, but it is also not likely to engage relative outsiders who may benefit from the knowledge and methodology. (I personally can’t absorb disparate sets of formulas, theorems, proofs across dozens of posters.)

We are living in a new age of communication. Formal letter writing has been replaced with emailing and instant message dings have become our background noise. Telephones travel with us everywhere but are often used for everything but calling someone. Facebook (Wait, now everyone is using Instagram?!). Snapchat (It’s gone?!). Twitter (You get 140 characters. No, wait! 280?) And how does one TikTok?

It can be hard to keep up, but it is essential to recognize there is a spectrum of communication platforms that have varied purposes and users.

Communication across generational styles can affect personal interactions and decision-making processes. How professionals in different roles and stages of their careers ingest, process, and distil information can be quite varied.

In Sticking Points: How to Get 4 Generations Working Together in the 12 Places They Come Apart, Haydn Shaw dives into each generation’s social factors and world events that affected their formation as individuals and a generation. These factors affect how, when, and why different generations communicate differently.

These considerations can be especially important as we “brief up the chain” in the management pyramid. (An informal instant message is likely not the best way to relay our cutting-edge analysis results needed for the important funding decision.) Those in more established roles looking to increase their scientific collaboration with young professionals could also take note. (The freshly graduated new hire with their attention seemingly buried in their device may be checking the latest project update, not ignoring the weekly status meeting.)

As data scientists, it is critical for us to learn how to leverage expertise across generations. As communicators, it is important to understand not only where our boss or employee is coming from but also how to design our own communication style to effectively reach across generations.

A piece on NPR’s All Things Considered, “To Save the Science Poster, Researchers Want to Kill It and Start Over,” introduces Mike Morrison, a doctoral student at Michigan State University who created a viral video in which he proposes a new poster design. According to NPR, “It looks clean, almost empty. The main research finding is written right in the middle, in plain language and big letters. There’s a code underneath you can scan with a cellphone to get a link to the details of the study.” It’s the 7–20-second soundbite on a poster!

This is not to encourage us to only use 7–20 seconds to relay our scientific work; it is to implement the engagement stage of the ERI model to generate audience interest, possibly leading to involvement via a further conversation or future collaboration.

What’s My Point?

The very nature of statistics as a scientific discipline requires good communication skills for effective collaboration and relaying of results. There are important nontechnical aspects to communicating across a larger audience and into the public domain.

Progressing through my career, the most useful skill I have developed has been the art of technical statistics communication with nonstatisticians. Solid and effective communication skills are essential to relaying information to nonscientific decision-makers and the public. We need to reframe the conversation and flip the paradigm to best communicate our point.

Dear prof. Mannshardt,

I’m the founder and past Chair of the Leadership-in-Practice Cmmttee (LiPCom) with the ASA Biopharmaceutical Section. Along with my LiPCom colleagues, we have put together a proposal to hold a leadership panel discussion session at JSM 2022. The title of our session is “Leadership for Impact”. The session will go for 1.5 hours and will consist of two 20min presentations, followed by an open discussion by a panel of experienced statisticians across industry, govt and academia. I very much enjoy your article, which we believe fits perfectly into the theme for our proposed session.

On behalf of LiPCom, i would like to invite you to please consider being one of the two pivotal speakers in our planned panel discussion session.

I would much like to speak with you to provide more information for you to consider. Would greatly appreciate if you could respond to me directly (abie.ekangaki@premier-research.com) so that we can arrange a time to chat. I am located in RTP.

Thank you again for an insightful article.

Kind regards,

Abie.