State of the Education Data Infrastructure: What Three Experts Have to Say About the National Center for Education Statistics

Steve Pierson, ASA Director of Science Policy

For the state of the data infrastructure series, the ASA Count on Stats team spoke with three experts on the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES): James L. Woodworth concluded his three years as NCES commissioner in June 2021; Jack Buckley was commissioner from 2011 to 2013; and Felice J. Levine is executive director of the American Educational Research Association and chair of the board for the Council of Professional Associations on Federal Statistics (COPAFS).

NCES, which is in the Department of Education’s (ED) Institute of Education Sciences (IES), provides objective, reliable, and trustworthy statistics about the condition of education through administrative data collections, statistical surveys, longitudinal studies, and assessments. Founded in 1867, NCES is the second-oldest and third-largest in budget among the Office of Management and Budget’s 13 principal federal statistical agencies. NCES’s combined statistics and assessment budget lines account for about $260 million annually.

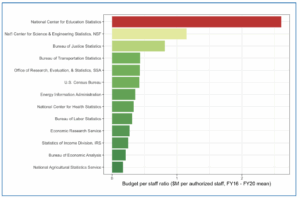

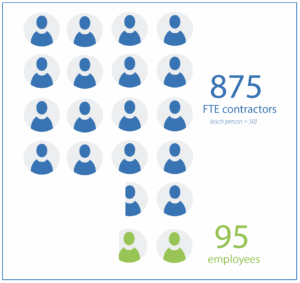

Contracting, staffing, budget, stature, and autonomy figure prominently in this exchange. For background, NCES has a budget-to-staff ratio of approximately $2.75 million per full-time employee—more than seven times the median ratio for the 13 principal federal statistical agencies—according to ASA-compiled data for the 13 federal statistical agencies (see Figure 1). This large ratio is explained by NCES’s heavy reliance on contractors, which Woodworth reported at a June COPAFS meeting as 875 full-time equivalents (FTE) to 95 NCES FTE employees (see Figure 2). The 9:1 contractor to employee ratio does not include the additional field staff needed for a big collection year like the upcoming 2021–2022 school year.

Figure 1: The budget to staff ratio for the 13 principal federal statistical agencies

Graphic by Jonathan Auerbach and Jordan Bryan

Figure 2: A schematic emphasizing NCES’s heavy reliance on contractors due to department-imposed staffing contractors

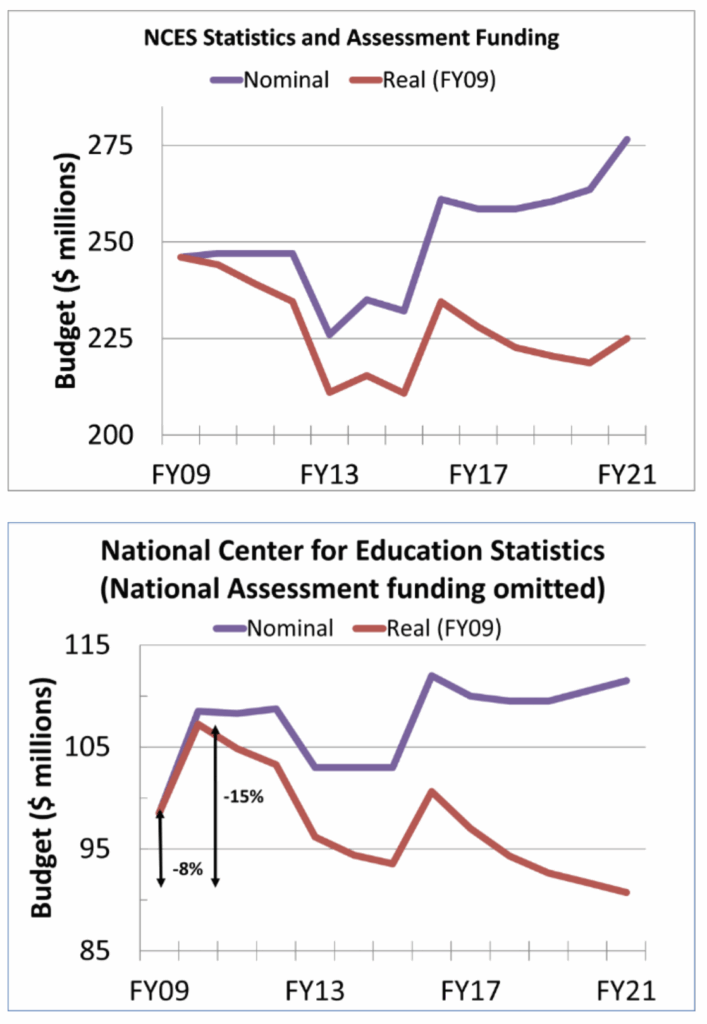

Figure 3: The total NCES budget (top) and statistics component (bottom) for FY09–FY21 in nominal and inflation-adjusted dollars

For contrast, the Energy Information Administration, which has an annual budget of $126 million (for FY21) reported at the same COPAFS meeting 359 employees and 300 contractors.

NCES has also lost 8.6 percent in purchasing power since FY09, though that amount has been reduced in recent years, as seen in Figure 3 (top panel). Much of the recent gains have been to NCES assessment work, which was funded this fiscal year at $165 million. The NCES statistics have been more stagnant, losing 15 percent in purchasing power since FY10, as shown in the bottom panel of Figure 3.

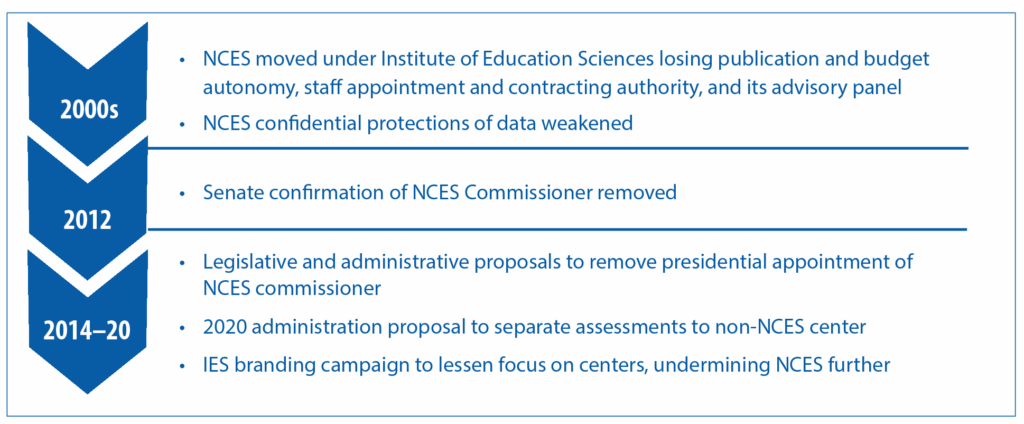

NCES has also lost autonomy and stature over the past two decades, undermining its ability to produce objective education statistics. NCES was moved under the newly created IES in 2002; its advisory panel was disbanded; and part of its budget, hiring, and contracting control was transferred to the IES director. A few years later, NCES’s authority to promise data confidentiality was weakened by the Patriot Act. In 2012, Congress removed the requirement of Senate confirmation of the commissioner, and there have since been several proposals to remove presidential appointment of the NCES commissioner. Finally, IES’s work to build its profile comes with diminishment of NCES’s profile. Figure 4 illustrates the NCES diminution.

The bottom line is that, despite the establishment of ED in 1867 “for the purpose of collecting such statistics and facts as shall show the condition and progress of education,” NCES in the 21st century has a relatively small profile within ED—some would also argue it is declining—and is hamstrung by overly burdensome bureaucratic constraints around hiring and contracting, declining purchasing power, and access to individual-level records. It nevertheless remains a vibrant agency staffed by employees who produce high-quality statistics and assessment and make important contributions to the broader federal statistical community.

Figure 4: Schematic illustration of reductions to NCES autonomy and stature since 2001 (Elchert/Pierson).

STEVE PIERSON: As the second-oldest statistical agency in the United States, NCES has a rich history of informing the decisions of students, families, and school districts. What are some of the agency’s most important contributions in recent years?

JAMES L. WOODWORTH: One of the most important things NCES does is help us understand the condition of education in the United States. Because education is a state’s right, rather than a federal activity, it can be difficult to make comparisons between states if you don’t have an agency collecting the data in a systematic way across the country. NCES plays a role that is unique among the federal agencies in that it works heavily with states to help them come up with common reporting measurements they do voluntarily.

FELICE J. LEVINE: When the federal government defined the role of NCES more than 150 years ago, it determined that understanding education in the US was essential to helping the states move forward. While NCES’s role has transformed over time, this function has remained enduring and essential. When you think about the leadership role of NCES, for example, with the development of the statewide longitudinal data systems—the SLDS—you can see very palpably how the agency catalyzed building quality administrative data systems with records and administrative data that otherwise could have sat in drawers or the electronic equivalent. We now have state longitudinal systems that can be meaningfully used by school districts and state education agencies, as well as by policy analysts, researchers, and other data users.

Let me also respond to Steve’s comment in our preliminary discussions that NCES products do not move the economic markets. I disagree. It does move markets over the long term. From early childhood and workforce data to the international assessments of adult competencies, NCES data are instrumental to understanding consequences of education on US health and our labor force. NCES has provided the backbone of so much of what we know in these areas.

JACK BUCKLEY: Where NCES is fascinating and unique compared to other statistical agencies is the assessment role. Even when you look at those that partially overlap with respect to adult education in the sciences, like NCSES, or with respect to the workforce, such as the Bureau of Labor Statistics, NCES is the only statistical agency in the United States that assesses cognitive skills of individuals at all levels, including adult learners. That role takes a lot of specialized scientific knowledge, working with a whole different suite of tools and constraints, and it’s very difficult to do well.

STEVE PIERSON: What are some of the most widely used or watched products from NCES?

JAMES L. WOODWORTH: NCES provides really unique products that are critical for understanding not only the education system, but the world as a whole. A good education system in our country directly relates to having a strong economy. These products can only be provided by having a centralized organization that is able to bring information in and put it out in a way that people can use. It makes the work NCES does collecting this data and the unified, unbiased, and politically neutral manner so critical and so important.

FELICE J. LEVINE: The longitudinal surveys that embrace all levels of education were well ahead of their time and remain invaluable for understanding educational experiences and outcomes, including long-term consequences. For example, ECLS, the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, is more than 20 years old and has been invaluable to improving education and understanding how family, community, and individual factors connect to education and educational outcomes. The longitudinal surveys have helped with understanding educational impacts not just in the short-term, but with a longer lens on workforce and health consequences.

JAMES L. WOODWORTH: Let’s also not forget the post-secondary world, where you have the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), an incredibly useful product that brings in information from all over the country in a way that’s comparable. The College Scorecard is also a very useful tool for families, especially those who have less knowledge about the post-secondary experience, such as first-generation college students like me.

STEVE PIERSON: How does NCES continue to play a role in policy and decision-making, not only through pandemic recovery, but in the next five to 10 years?

JAMES L. WOODWORTH: NCES has to become more nimble. It needs to balance accuracy with timeliness. We made significant progress on this during my time as commissioner, but there is more work to be done to be able to respond to things that happen in real life like COVID-19 or the next crisis that hits. Decision-makers need to be able to quickly access information about the schools and about the impact. It’s not enough to collect the data rapidly. You can’t spend a year processing it. You need to turn it around fast. When the pandemic hit, because of bureaucratic hurdles, it became clear to us that it would be a year before we could provide new products, and the nation at that point didn’t think the pandemic would last that long. Thankfully, Congress has helped us in the meantime to provide funding and two FTEs for the School Pulse Survey to be in the field this fall. It will collect data monthly and provide very quick turnaround.

JACK BUCKLEY: I agree. The Newtown, Connecticut, school shooting happened while I was commissioner. I was the only person left in the office and we got a call from the White House saying we needed to know right then the percentage of schools that had armed guards. I had to unlock the data cabinet and run the analysis myself. In this case, we were fortunate that we had a relevant data collection on school safety, even if we hadn’t reported this particular statistic previously. It’s a bigger problem, of course, if you don’t have the data already. Many years ago, NCES put in place a fast-response survey system, and the agency has since made some progress in that area. Nonetheless, we need to figure out how to remove some of the bureaucratic barriers and increase the capacity of the agency to be more agile and produce more timely and relevant statistics. We need to continue to build the sort of “muscle memory” that makes NCES more responsive.

FELICE J. LEVINE: There are many users who wish data were accessible faster and sooner. But in my own experience with the suite of federal statistical agencies, NCES has led over decades in access to public use files and procedures for allowing data users access to restricted data sets, with high levels of data protection and security. NCES also continues to be forward looking in offering public use dashboards, downloadable files, and other tools. Could they be more “muscle” ready as Jack notes? For sure, but I think the ambition for rapid, independent reporting is there.

JAMES L. WOODWORTH: Incorporation of response process data in NAEP also has enormous potential for assessment. Thanks to technology, we can record information such as time to respond to a question and whether a response is changed, which will give us insights into how students think. NCES is bringing in different forms of expertise to understand student decision processes.

STEVE PIERSON: What are some of those bureaucratic barriers?

JAMES L. WOODWORTH: One of the core problems is that NCES has to contract out so much work because the staffing is tiny. That creates a lot of problems. It means you don’t have the ability to innovate and experiment with new things. You have to run the old systems while you’re developing the new systems, so you can compare to make sure they’re compatible. If you don’t have any slack and you don’t have any staff overhead time that you could apply to innovations, then you don’t get innovations. In addition, NCES doesn’t even have an IT person. One consequence is the agency doesn’t hold the data on its own systems anymore, because they don’t have the capacity to manage a highly sensitive system.

That’s where NCES is right now; there’s just not enough overhead. NCES’s staff is phenomenal. Their work ethic is amazing. What NCES is able to accomplish with wrangling all these contracts and work, while still managing to move forward and push the boundaries on some topics, is because of the fantastic staff. That is key. NCES really does have an excellent staff; it’s small but great.

FELICE J. LEVINE: The innovation and good work NCES has accomplished comes with tremendous casualties and losses along the way. There are not enough resources. We’ve mentioned the heavy reliance on contracts, the low staff size, the absence of sufficient funds for vital data collection or reinvention of data collection, including the National Survey of Postsecondary Faculty that was put on a back burner. The information we had on community college faculty, four-year institutions, and those without doctorates in other environments are lost assets. We know today how much we need that information as we rethink what higher education and technical training should look like.

JACK BUCKLEY: There is room for reinvention and some bureaucratic streamlining to reduce the many, many months of the lead time it takes to make a change in an NCES collection. And that’s not driven by the fact that the agency doesn’t have enough staff. It’s driven by the fact that one needs to follow a very precise set of instructions in order to make even a small change to a survey instrument. I think this is very important sometimes for quality, but in other cases, it negatively affects the agency’s ability to be flexible. When I was there, we tried and failed to get more autonomy in contracting, even if it meant having contracting authority delegated to IES. Having contract officers at the IES or NCES level would have improved that bottleneck, which I can imagine has only gotten worse as the rest of the Department of Education has shrunk.

JAMES L. WOODWORTH: What Jack mentions is indeed an additional layer of burden to the heavy reliance on contractors. The bureaucratic challenges within the department of having the contract approved is a big bottleneck. I do want to credit that OMB’s work for approving NCES work through the Paperwork Reduction Act (PRA) is remarkably efficient and smooth, owing in part to the quality of NCES PRA packages. The bureaucratic challenges within the department are much more a cause of delay.

STEVE PIERSON: Is there one thing you think would be a game changer for NCES?

JAMES L. WOODWORTH: The big game changer for NCES would be the passage of the College Transparency Act and allowing NCES to collect more individual record–level data, which NCES is prohibited by Congress from collecting. And that makes it really hard to do analysis, especially post-hoc analysis, and verification of the data. It’s also more challenging for the institutions that have to report more fields of data. Even members of Congress are sometimes disappointed, asking why NCES can’t release data in the way the Census Bureau does. It would be very helpful if NCES had a little more ability to collect individual record data, even the de-identified individual record data would be more useful than how we collect the data now.

FELICE J. LEVINE: I agree. Passage of the College Transparency Act would be a real plus. In addition, I think a game-changer would be some innovative thinking about how we deal with low response rates and serious consideration of the very real trade-offs between administrative data and primary data collection. Where NCES has led and can further lead is to work through the complexities of data linkage, so we also don’t collect data that can be ascertained elsewhere. Such advances would make a difference in moving forward; reducing response burden; and getting the quality information school leaders and teachers, faculty at all levels, school districts, and the higher education and research communities need.

JACK BUCKLEY: I agree that it would be untying the agency’s hands from behind its back with respect to unit record data collection at the population level for all students. One of the great privileges of being commissioner was representing the United States in international settings around education data. There was never a time I mentioned to ministers in similar roles from other nations that the United States did not have a population register of its students and couldn’t track them through their educational experiences that their jaws wouldn’t fall open. Meanwhile, our high technology company sector is tracking their citizens through their entire lifetime experiences.

STEVE PIERSON: Please speak to the downward layering, the loss of presidential confirmation, and any other autonomy stature issues going on.

FELICE J. LEVINE: The role of the NCES commissioner to advise the secretary of education and IES itself on the evidence base of policies or research program priorities gets lost with, as Bob Groves put it more broadly, the downward layering of federal statistical agencies.

The pathway of the commissioner reporting independently to the leadership in the department has been lost and eroded over time. That is an unintended loss, in particular with the passage of the Presidential Appointment Efficiency and Streamlining Act of 2011. It was not targeted at NCES; it justifiably removed Senate confirmation for hundreds of positions but NCES was collateral damage. Hard to believe it has been 10 years; we hope to hold on at least to presidential appointment in any IES reauthorization.

JACK BUCKLEY: I agree that it was unfortunate. If I had to choose one thing, however, contracting autonomy would be more important to me than Senate confirmation. That doesn’t mean I don’t agree, but I think on the scale of challenges, it’s minor relative to staffing and contracting red tape.

JAMES L. WOODWORTH: I do also feel that the loss of Senate confirmation did result in a loss of stature for the position. Anyone who has ever dealt with the government understands that’s pretty critical. The level of importance of your position carries a lot of weight, especially when you have a new person coming in or an administration changes. There were times when I had to say no. I did not always agree with the politicals and what they wanted to do. The fact that I could say no with confidence was important. I’m shocked that I actually made it through the duration of my term, and I think a lot of that was due to the fact that it’s pretty hard to fire the commissioner.

It’s also really important that you have an independent statistical system. The fact is, in American democracy, we change parties and leadership and both the executive branch and the legislative branch so regularly. You need people who are collecting the data, collecting in a consistent manner, and not shifting the focus to suit the needs, both in a positive and a negative way for the sitting administration or the sitting Congress. It is important that you protect the role of the statistical agencies, and one way you do that is by keeping the head of the agency in a position that has seniority attached to it. Being a presidential appointee definitely adds to that. Every layer of bureaucracy above a federal statistical system is another layer of bureaucracy that thinks they have a legal right to interfere with the operations of that statistical system. Unfortunately, they do exercise that perceived right when I think the law is clear they are wrong.