State of the Nation’s Health Data Infrastructure: Experts Weigh in Two Years into Pandemic

The State of the Data Infrastructure Series frames the federal statistical agencies as the backbone of the US data infrastructure. Just as our transportation infrastructure supports the US economy, governance, and society, so too do the federal statistical agencies.

While praising the work and advances of NCHS since the start of the pandemic, Jennifer Madans, Ninez Ponce, and Charles Rothwell discuss how the pandemic also exposed the agency’s challenges with budget, stature, and profile.

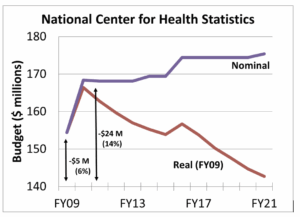

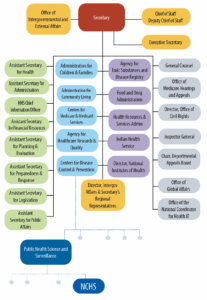

NCHS’s loss of purchasing power, as illustrated in Figure 1, is the greatest challenge, keeping NCHS from maintaining its four main data programs—vital statistics, interview surveys, examination surveys, and provider surveys (see Figure 2)—while also meeting data-user demand for more granular and timely data and integrating data from multiple sources.

The experts also discuss NCHS’s relatively low profile within its parent agency, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)(see Figure 3). As a subunit of one of the components of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), NCHS is several administrative layers from the HHS secretary. This is notable given that the Evidence Act designates the NCHS director as the HHS statistical official “to advise on statistical policy, techniques, and procedures” and stipulates, “Agency officials engaged in statistical activities may consult with any such statistical official as necessary.” NCHS’s organizational position makes it difficult for the agency to fully meet the data needs of HHS or the requirements of a federal statistical agency.

Finally, Madans, Ponce, and Rothwell share their vision for the NCHS’s role in the public health data landscape, which is being transformed by more demands for data, more suppliers of data, and therefore more sources of data.

~ Steve Pierson, ASA Director of Science Policy

Please describe what you see as NCHS’s most important role in US public health and its greatest strengths.

Jennifer Madans served as the NCHS associate director for science, acting deputy director, and acting director, retiring from federal service in December 2020.

Jennifer Madans served as the NCHS associate director for science, acting deputy director, and acting director, retiring from federal service in December 2020.

Ninez Ponce is a professor of health policy and management in the University of California at Los Angeles Fielding School of Public Health and the principal investigator of the California Health Interview Survey, the largest state health survey in the United States. She was a member of the NCHS Board of Scientific Counselors from 2017–2020.

Charles Rothwell was director of NCHS from 2013–2018, capping a career in federal service that started in 1987.

Charles Rothwell was director of NCHS from 2013–2018, capping a career in federal service that started in 1987.

Ninez Ponce: First, let me comment that I love that you call this the State of the Data Infrastructure Series. For me, data—particularly public health data—is infrastructure, a public good for which NCHS is known as the gold standard.

As an administrator of a survey here in California, NCHS surveys are important as a benchmark of how we are doing compared to others nationally. For example, how do California diabetes rates compare to the national rates? This is an important way NCHS is making an impact on the lives of Californians.

As far as NCHS and the pandemic, I think NCHS’s vital statistics system has been functioning very well and, in some ways, was my go-to for COVID data. This is not to say, as I’ll discuss later, there wasn’t more I would have liked it to provide. Nonetheless, I believed in the information from that system more than what was being put out from other federal sources, which also, of course, speaks to the coordination of COVID data.

Jennifer Madans: The vitals program is indeed important and likely the most well-known of the NCHS data collection programs, but the three other survey programs—the interview surveys, examination surveys, and family of provider surveys—are just as critical. All four major systems and their associated enhancements, such as linkages to other sources, are needed to obtain core data on the multiple aspects of health and health care required to develop and monitor initiatives to improve the health of the population.

Building on Ninez’s point about the role of NCHS’s vital statistics program during the pandemic, it is important to acknowledge the data was trusted because of the system’s long history of providing high-quality, unbiased data with extensive documentation on how the data is obtained, processed, and coded. The program’s transparency and adherence to standardized rules that data users know and understand are what makes it a useful and trusted data source.

Unfortunately, the pandemic also exposed NCHS’s weaknesses, which are direct results of a history of stagnant funding, particularly over the last decade or so. I know we’ll discuss the impact of lack of funding in more depth later, but we also need to highlight how much NCHS has been able to accomplish with such a strained budget. This is a testament to the commitment, expertise, and resourcefulness of the staff and gives assurance that even a modest increase would allow the agency to do so much more to advance the core database. A more substantial increase to support greater innovation and expanded breadth of information collected would be well worth the investment.

Charles Rothwell: I wholeheartedly agree that what the NCHS staff has been able to accomplish with diminishing resources is astounding. Through adversity, the staff has become more creative and willing to try new approaches to providing the health status information this country needs. It is definitely time to invest in an improved and trusted health statistics infrastructure for all levels of government to fill the data gaps exposed by the pandemic and the demand for more timely, frequent, and granular data. NCHS has shown time and time again that it can make the most of the funding it receives. Let’s put our bet on a sure thing!

To build on Jennifer’s point about what could be done with a little more funding, consider the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) when NCHS was quickly able to use newly available funding to expand data collection in the National Health Interview Survey, providing quarterly estimates and monitoring outcomes in more than 20 states. With little funding, NCHS was able to test and add questions, go from late annual national reporting to quarterly reporting of the impact of the ACA on health insurance coverage nationally and for many states, and deliver quality health status data, including on the most vulnerable population groups. Similar gains in timeliness and dissemination were made as a result of limited funding targeted to monitoring the opioid epidemic.

Elaborate on the challenges from the underinvestment in NCHS.

Jennifer Madans: NCHS has become severely compromised due to lack of funding. As a result, the organization has had a hard time providing the data needed to monitor the pandemic. As there was no funding to proactively invest in expanding and modernizing core data collections, the agency instead had to react to changing data needs as best it could while maintaining ongoing collections.

Perhaps the largest and most damaging data gap involves the health care surveys, where the need for data was greatest but where there was no infrastructure to provide data to monitor the impacts of COVID-19. A close second is the reduction in sample sizes for the survey programs, resulting in the lack of data of population subgroups needed to address equity issues related to the pandemic but which are also critical for all aspects of health and health care.

The reduction in sample sizes reflects not only reduced purchasing power but also the added costs of addressing diminishing response rates, something all surveys have experienced. Declining response rates impact multiple aspects of data quality and need to be addressed through expanded and modernized collections practices, as well as methodological advancements in how to evaluate and address any remaining bias.

Another casualty of lack of funding has been the loss of analytic capability. As a result, the agency has been challenged to produce more in-depth analyses that would inform policy. To address these gaps, the base budget must be increased to ensure NCHS fulfills its mission to collect, analyze, and disseminate trusted data in a way that is useful for a wide range of constituencies.

Trusted data available when needed and with sufficient specificity is what is required of an infrastructure that can inform decision-making at all levels of government. This infrastructure needs to not only be built back, but built back better.

Charles Rothwell: NCHS has not been able to keep up with the latest advances in technology. When the pandemic began and NCHS’s data collections could not be conducted in person, the agency didn’t have fallback mechanisms in place to adapt to the new conditions quickly and seamlessly. There had been experimentation using web panel surveys and electronic health records, but because of the overall lack of funding for NCHS, these innovations—which could have helped considerably—had not progressed far enough to meet needs.

There was and remains a paucity of information available about nursing homes, assisted living, and extended care facilities. We didn’t know the staffing issues in these facilities, and we knew little about the health status of residents in these facilities who, as it turned out, are at highest risk. The health care information collected by NCHS and elsewhere in HHS needs to be brought together and made more available. This should be done by NCHS because of the many statistical issues involved and the unique perspective of a statistical agency.

Furthermore, we need to look at COVID from more than a national public health perspective. COVID has shown us we are a connected society that differs from community to community and state to state. Public health actions affect not just our physical health but also mental health, education, work life, and the economy for all of us. We need to collect and provide timely data for states and communities to make appropriate and timely decisions to meet their needs. This should have been an effort NCHS and the other statistical agencies could have led at the outset. I will say though that the pulse survey led by the Census Bureau and other statistical agencies—although late in the game, not as extensive as needed, and limited in terms of representativeness—is an example of what could have been done if we bring together our survey capacity using the latest technologies.

Ninez Ponce: Before COVID began spreading, there was a demand for more granular data on race, ethnicity, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, etc. With the data collection challenges that occurred during the pandemic, identity data became even more sparse, leading to more inequities. In addition to needing more resources to collect that kind of information, I also think there needs to be investment in NCHS surveys, because they are a portal into what pains Americans are experiencing.

You’ve mentioned the burgeoning demand for more granular data in terms of demographics, geography, and frequency. What is driving the demand, and how would you justify the costs for providing such granularity to the American people?

Charles Rothwell: As COVID spread in the US, not all areas of the country experienced surges at the same time. They were hit in waves. Governors and localities didn’t have specific enough data to make nimble and focused decisions. Unfortunately, because of the diminished sample size for NCHS surveys Jennifer mentioned, the surveys were unable to provide granular information on the pandemic that could have informed those decisions. This is something we really need to address.Furthermore, if granular information is collected, that data needs to be provided to those who are going to use the data in close to real time, rather than just producing a late and not very usable report.

When I was on the National Academies committee looking at improving morbidity and mortality reporting during and after disasters, including pandemics, we learned that even when localities were getting federal and NCHS data, many times they didn’t have the staff to examine it closely and the data was not in a usable format for quick action. NCHS doesn’t have the staff and systems to provide such support, including how best to use the data, but it should.

Ninez Ponce: In California, there was an equity metric included when determining reopening businesses and schools. There were additional requirements to make sure the case positivity rates for the areas that posted the poorest social determinants of health or high poverty rates of a county also met a certain criterion for the county to reopen.

The local area-based metric helped to assure economic recovery was happening across all communities in each county. But, like all metrics, they may have blind spots for smaller, more geographically dispersed communities like American Indians, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders.

Decision-makers need to understand how to use and augment these area-based metrics to better target resources, recovery funds, and community organizations in need of support so they can close the equity gaps and accelerate recovery rates. Expanded partnerships between NCHS and state-based data collections would facilitate the development, use, and interpretation of area-based indicators such as the equity metric.

Jennifer Madans: Data linkages—the linking of NCHS data to other data sources—has a role here. For example, linkage could be done with data from other sources that address social determinants of health and health care. Like politics, health and health care are local. Data granularity is essential to make the most use of information on social determinants, as the pandemic made clear.

Charles Rothwell: Data linkage is an outstanding example of what underfunding will do, even if one tries to be creative. NCHS has one of the most useful data files in government that, when linked to other data sources, can be used to examine the impact of government programs and actions on mortality, especially regarding the most vulnerable. It is called the National Death Index and has data on every death in the United States, including the information needed for linking.

The index remains unfunded in appropriations and so, to reimburse the state systems for providing the data and supporting the linkage service, NCHS must charge for these data linkage services. These charges have made it cost prohibitive for linking to large databases or for agencies serving vulnerable populations to use. If NCHS were able to freely provide the linkages, we would see an expansion of valuable insights into social health determinants and other public health policymaking discussions for HHS, other agencies, and the research community.

The need for more health data has been a prominent lesson from the pandemic. Many private entities helped to meet the need. Going forward, how do you see NCHS’s role in the broadened health data landscape?

Charles Rothwell: I’d like NCHS to produce more regularly updated ‘living’ publications like they are now doing on excess mortality, COVID, and drug overdose deaths. Rather than only offering annual reports, let’s have monthly—if not weekly—data releases where appropriate. Those reports need to be ‘friendly’ enough that an uninitiated user can easily look at the data and obtain community-specific information. We should also provide support to the data users, teaching them how to use the data appropriately.

Jennifer Madans: The plethora of other data sources underscores the vital role of NCHS as a trusted source and the need for a mechanism to evaluate the quality of data from other sources. With volumes of data being released, how do data consumers know which to believe or how to combine them to paint a comprehensive picture? NCHS could make a major contribution by providing standardized definitions and methods for use by other data producers, along with quality metrics for data users. Most importantly, NCHS should provide the basic infrastructure that can be built upon by other data providers. As has been done in the California Health Interview Survey, geographically focused data collections can build on the national collections. The result would be a stronger national infrastructure and a trusted data infrastructure for all levels of government.

We also mentioned that NCHS’s vital statistics data was trusted and considered the gold standard. The other data systems need to be revitalized so they can support the broader health data landscape. This will take funding and leadership.

Regarding dissemination, NCHS has been catching up in making interactive data more readily available. But to publish data with maximum frequency, NCHS must have the resources to collect the data needed to provide reliable estimates. This requires an expansion on sample sizes for all surveys, which also allows for greater granularity for population subgroups, even if data releases cannot be made on as frequent a basis.

In addition to disseminating data more frequently and with greater granularity, NCHS should produce more methodological publications that explain how data is collected, processed, and analyzed. Included in this is the minimum set of data elements that should be available for all population subgroups defined by sociodemographic characteristics or by geography. As new data needs emerge, the core systems can be modified to collect the new elements. Without that underlying data infrastructure, it is not possible to address emerging needs. A statistical agency needs to do more than post some interesting graphs on the web.

Ninez Ponce: In my perspective, to produce more frequent and granular data requires representation and democratization to ensure NCHS’s gold standard of data production is maintained. The data produced by the federal data system that monitors health represents the health of the nation. I agree there should be more partnerships with other data sources. It should be the government’s role to track COVID-19 deaths and cases by race and ethnicity. There’s also a federal role to listen to what data social movements are looking for to make a better system of reporting.

What are NCHS’s other primary challenges?

Jennifer Madans: While politicizing at NCHS has never been at the same level as found at some other statistical agencies, interference does occur and had been increasing during my last several years of service. This is to be expected as the data collected became timelier and policy-relevant.

Interference tended to occur regarding the timing of releases. Guidance on the practices a statistical agency should follow regarding the release of data or reports is provided by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and is critical to maintaining the independence of statistical agencies. There have been times when NCHS would announce a planned release of a report for a specific day, as required by OMB guidance, and there would be suggestions to either speed up the release or postpone it. Following OMB guidance, release dates were never changed but it would be ideal to have a stronger OMB and a stronger statistical system that can provide the needed protection and institutionalize this protection.

The deeper a statistical agency is buried in an organization, as is the case with NCHS, the harder it is to protect the agency’s independence and for the agency to contribute to a robust data infrastructure. It is key that the statistical agency be included when structuring the data collection systems of both the department where it is located and the entire federal system. While this can be done even if the agency must report through multiple organizational levels, the ability to do so is dependent on the priorities of those controlling those reporting levels, and the viewpoints of those controlling the interactions can change often and in negative ways. It is far better to support the statistical agency with proper organizational placement, which in turn will better serve the host department’s evidence-based policymaking.

Let’s go back to the COVID-19 example in which the credibility of the data became hugely important. If users don’t believe the data and those responsible for providing the data infrastructure are not able to prepare for future data needs, then the whole society is in the dark. It doesn’t matter how granular the data is or how fast it is released; if the data doesn’t have credibility or reflect data needs, it will not be used to inform policy.

Charles Rothwell: I agree with Jennifer. NCHS needs improved visibility within HHS and with the public. I used to be proud to say we are the best government agency you have never heard of. That statement, although still true, is now nothing to be proud of. NCHS is not seen by many in HHS as the federal statistical agency for the department. Most see it as a data arm for CDC-centric activities. As important as CDC is, NCHS’s statistical role encompasses HHS-wide activities, as indicated by its data leadership in the Healthy People Objectives for the department and its leadership in the HHS annual report to the nation on its health status—Health US.

Also, for NCHS to be known to the public as a credible source of information, it must be given credit for the data in the media instead of giving the credit to a parent agency. What we are suggesting cannot happen without funding and legislation aimed at strengthening the role of NCHS.

On a hopeful note, Congress has recognized these issues. The Health Statistics Act of 2021 recognizes NCHS as the focal point for expanding data sharing and data linkage throughout HHS, explicitly incorporates the National Death Index in the effort, and creates data standards to make the analysis of combined data files more useful.

How could proper funding and support better position the country to recover from COVID-19 and be ready for the next pandemic?

Jennifer Madans: With adequate funding, it will be possible to build an infrastructure that rapidly releases relevant and reliable information, including for subpopulations of interest. Additionally, funding would allow stronger connections with state health departments, the academic community, and foundations collecting information on the same issues. Investments in NCHS would put the agency in a better position for not only the next pandemic, but for everyday data collection and analysis activities.

Charles Rothwell: While we do want to prepare for the next pandemic, we’re not even measuring current data on a quick enough basis. We need to be assessing the major causes of death, current major illnesses, and the health disparities taking place in our country from a granular perspective. That can be done by improving the individual survey components and building new ones. With the health care surveys, data is released much too slowly. The reports say little about the current status of the nation and little about states or communities.

One of the biggest challenges we have at the moment is the use of electronic health records. If NCHS was more involved, statistics would be based on tens of millions—if not hundreds of millions—of health records, instead of thousands. Doing this will take a huge amount of work from a quality and standardization perspective, but it is necessary to make data more granular and timelier. To accomplish this, it will take money, staff, and technology.

Ninez Ponce: The collection of race and ethnicity on electronic health records is terrible. Approximately 70 percent of the fields for race and ethnicity are missing. I do think there is room for additional questions on race and ethnicity in surveys, which is why we still need surveys. Previous investments were how we were able to redesign and continue collecting data a few years before the onset of the pandemic. If NCHS had more money to conduct experiments, pull ideas, and have linkages, then they could be ready for what is next.

Jennifer Madans: That also goes back to NCHS needing to have big enough survey samples to provide granular data and have a basis on which to address emerging data needs. There is a lot of talk about the need for more granular data but there has not been a commitment to pay for it. What it comes down to is, if you want the data, you need to pay for it.

To meet these challenges and demands, besides additional funding, what does NCHS need from Congress and the administration?

Ninez Ponce: Local data is critical, and I’m not sure if NCHS can get at local data outside of vital statistics. Perhaps investing more in small area estimation estimates of the surveys for subnational localities—such as states—would be valuable data to spur local action. The federal surveys need to be better supported to have a large enough representative sample of the US, to include relevant content, and to disseminate quickly. The federal surveys are important, again, as a benchmark of how states and possibly large counties are doing compared to others nationally.

Charles Rothwell: I agree with Ninez on the problem for NCHS with local data, and it reminds me of a huge missed opportunity many years ago and one that should be reconsidered. When I came into government in the 1970s in a state health department, there was a federal program called the Cooperative Health Statistics System. The intent was to improve health statistics at the state and local levels, thereby expanding trusted data available for improved policy decisions at the national, state, and local levels. State-based interviews surveys and health care surveys were initiated in several states, as well as the creation of state centers for health statistics. This program was funded by NCHS, but the funds quickly disappeared and the program died an untimely death. Just think of where we would be now if that program would have survived and thrived in all states. I think it is time to, once again, build strong statistical partnerships in public health at the state and federal levels beyond vital statistics and reconsider the Cooperative Health Statistics System.

Additionally, I think surveys are vital and need to be maintained as the gold standard of the federal statistical system. We do need to make better use of administrative data both within government and the private sector, as these are important and growing sources that can expand our survey capacity. As data comes available from a variety of sources, we must use it to improve the depth of the information we are providing, but we will need surveys to ensure we are not missing people who are not using the services generating these large data sets and who may be the most vulnerable.

At the national level, I know this sounds avant-garde for federal statistical agencies, but I think that with the technologies currently existing, we can remain decentralized at our various departments and be virtually centralized, reporting to the chief statistician of the United States in OMB. All statistical agency directors would report to both the appropriate senior official in their department and the chief statistician. This would allow the statistical agencies to remain within their respective departments, meeting the needs of the agencies within their department but also having the support of a virtual government-wide organization with similar roles and needs and with direction and coordination from a centralized person at OMB. For this to happen, the Office of the Chief Statistician needs to be strengthened both from staffing and visibility perspectives. What better time to consider this as a new chief statistician is about to be selected?

Jennifer Madans: I think NCHS needs ongoing budget support and the mandate to move forward in developing a high-quality health data infrastructure. The current budget and organizational placement have not been supportive of these goals. HHS and the federal statistical system would benefit from a stronger and expanded NCHS and more engagement with the agency, particularly in regard to strengthening the role of the statistical official. Past lack of engagement resulted in loss of purchasing power, the inability to expand data collections as needed—especially in regard to timeliness and granularity—and the failure to adopt innovative data collections platforms. To “Build Back Better” needs to include a transparent, credible health and health-care statistical infrastructure.