National Center for Education Statistics Faces Program Cuts

Daniel Elchert, ASA Science Policy Fellow, and Steve Pierson, ASA Director of Science Policy

As reported by The Washington Post, the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) may cut or reduce several programs unless the Department of Education (ED) and Congress intervene to provide needed resources. The agency’s depreciating budget and low staff number are longstanding challenges that have reached a potential tipping point.

The ASA needs your help to ensure we are aware of and understand the varied challenges facing statistical agencies. To get involved, contact ASA Director of Science Policy Steve Pierson or ASA Science Policy Fellow Daniel Elchert.The ASA would especially appreciate your help to support NCES. You can help by making your US representatives and senators aware of the agency’s challenges and urging that they address them. You can also help by sharing this article with your network or by letting us know how NCES data inform evidence-based policymaking in your community or state.

As Congress and the nation respond to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, NCES will have an important role. Given the profound influence of COVID-19 on students, parents, teachers, administrators, and policymakers, high-quality and relevant education statistics will be vital to a full and effective recovery.

Background

Among the oldest and largest of the principal federal statistical agencies, NCES is in the ED Institute of Education Sciences (IES). NCES’s historic mission dates to 1867 when the US Department of Education was founded. Using surveys, assessments, and administrative data, the agency compiles, analyzes, and reports education information throughout the United States and across the globe.

Some of this work, such as the annual Condition of Education report and National Assessment of Educational Progress, is mandated by Congress—meaning the agency must report objective education data that can be used by policymakers, administrators, and the public. However, several key programs are in jeopardy due to the agency’s staffing and budget constraints, including the School Survey on Crime and Safety (SSOCS), Fast Response Survey System (FRSS), Baccalaureate and Beyond Longitudinal Study (B&B), and High School Longitudinal Study (HSLS).

To briefly explain the importance of these programs, SSOCS provides data on incidents, security staff, and mental health services in America’s schools. FRSS is a mechanism for rapid response data on current and critical issues in the education pipeline, which could be a critical source of information about school responses to COVID-19. The B&B tracks college and post-college employment and education experiences in addition to providing data on graduates entering the teaching profession. The HSLS reports statistics about ninth-grade students from the year 2009, describing their trajectories in subsequent stages, including high school, employment, and college.

Problems

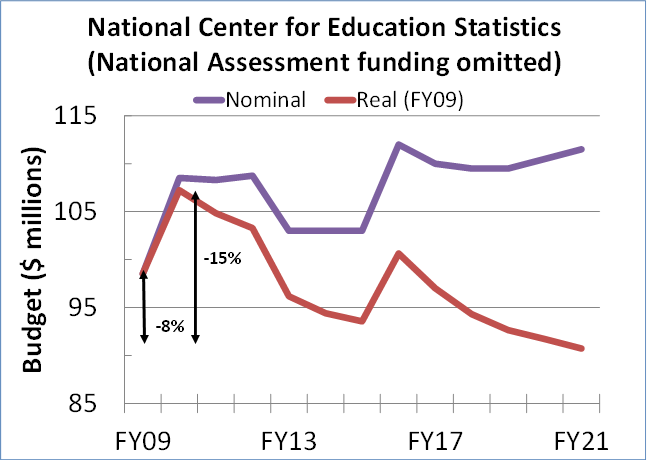

Two main problems threaten NCES programs. The first involves the agency’s budget, which is provided through annual congressional appropriations and has two parts: the assessment line and the statistics line. As shown in Figure 1, the statistics line has depreciated in value more than eight percent since fiscal year 2009 (FY09), making it increasingly difficult for the agency’s statisticians to monitor, collect, analyze, and report on education topics that affect the lives of students across the country.

Figure 1: The NCES statistics budget in nominal and inflation-adjusted (i.e., real) dollars, showing the $8 million loss in purchasing power since 2009. Data source: Statistical Programs of the United States Government, OMB, FY11-FY20

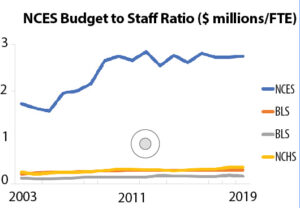

As the agency’s statistics line has gradually lost purchasing power across time, so too has its number of full-time equivalent (FTE) staff declined, which is the second driving factor behind potential program cuts. In 2000, the agency had 115 FTEs, whereas today there are fewer than 95. This decrease in FTEs has by no means been linear, but has nonetheless deteriorated substantially. With an FY20 budget of $264 million when including the assessment and statistics accounts, NCES has a budget to FTE ratio of approximately $3 million per employee, which, as shown in Figure 2, is about nine times the median of other large principal federal statistical agencies. While statistical agencies may use their staff in different ways, the magnitude of this discrepancy suggests NCES is understaffed relative to other agencies that collect, compile, analyze, and report official data.

Figure 2: The ratio of the NCES budget to the number of full-time staff since 2003 as compared to three other agencies: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), and National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). This figure does not indicate that any particular agency has sufficient staffing. Data source: Statistical Programs of the United States Government, OMB, FY05-FY20.

Consequently, NCES’s budget-to-FTE staff ratio may undermine the agency’s ability to cost-effectively lead and oversee education statistics programs. Many, if not all, statistical agencies contract out some of their work to non-government organizations, but this pattern may have gone too far in the case of NCES. This problem could worsen if NCES employees who retire or vacate their positions are not replaced in a timely manner, leading to diminished in-house expertise and technical knowledge, less efficient use of taxpayer money, and too few staff to manage contracts effectively.

The NCES staffing shortage is at least partly due to the ED budget structure, along with hiring freezes and other bureaucratic delays. In other words, NCES cannot simply use money appropriated by Congress to hire more statisticians. Instead, NCES and IES staff are part of a large, undifferentiated, salaries and expenses (S&E) budget account for ED administrative costs.

In addition to these budget and personnel challenges, NCES has lost autonomy and stature over the past two decades, which threatens its ability to produce objective education statistics. As outlined in OMB Statistical Policy Directive #1 and the National Academies’ Principles and Practices for a Federal Statistical Agency, a federal statistical agency should have authority over its budget allocation, information technology, hiring, and publications to ensure independently produced statistics and to avoid even the perception of inappropriate external influences on statistical activities.

In 1988, the Hawkins-Stafford Elementary and Secondary School Improvement Amendments Act provided NCES autonomy to ensure objective and reliable NCES products. For example, it made the NCES commissioner presidentially appointed and Senate confirmed, which helps ensure the administration and members of Congress contribute to the selection of a highly qualified leader. Presidential appointment and Senate confirmation also provide the commissioner with more authority to advocate for the independence, objectivity, and relevance of NCES data.

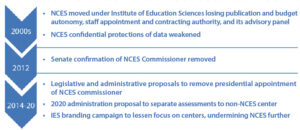

Figure 3: Schematic illustrating series of reductions of NCES autonomy and stature over the past two decades

As illustrated in Figure 3, NCES has been slowly losing such protections since 1988, threatening its ability to produce high-quality, objective data. NCES was moved under IES after the institute’s legislative creation in 2002, leading to the disbandment of the agency’s advisory panel and partial transfer of its budget, hiring, and contracting control to the IES director. In the same decade, some of NCES’s authority to promise data confidentiality—a mandate reinforced today by Title III of the 2019 Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act—was weakened by the Patriot Act. Despite these challenges, however, NCES has remained consistent in ensuring the confidentiality of data it collects for statistical purposes.

The weakening of NCES’s authority continued in 2012 when the commissioner’s Senate confirmation status was removed as part of a broad effort to address hearing delays for hundreds of federal positions. There have since been several proposals to remove presidential appointment of the NCES commissioner, including by the current administration in its FY21 budget request. The budget request, which is typically a statement of an administration’s funding priorities, takes the unusual step of including a reauthorization proposal that would separate out NCES assessment activities to a new IES center, a substantial organizational change that could further deplete NCES’s annual budget. As the NCES loses authority across time, it is susceptible to further weakening.

Addressing the Problems

Some of these problems could be addressed by ED officials, while others would require congressional action. In principle, the low NCES staff number could be partially ameliorated through carefully implemented ED administrative action to grant the agency more FTEs. Raising this level in one ED agency could mean reductions in another, complicating the nature of any such move because of personnel issues across the department.

Congressional appropriators could also help address NCES’s staffing issues by seeking a set-aside for NCES from the ED S&E budget to list the agency as a separate account, as is done for the Office for Civil Rights and Office of Inspector General. Appropriators could provide relief to the NCES through direct budget increases to its assessment and statistics lines, but this is likely to be difficult considering thin margins for nonmilitary discretionary funding and money needed to support the nation’s COVID-19 pandemic response. As the education pipeline recovers, NCES is well-suited to contribute positively to this effort. For example, NCES’s Fast Response Survey System (FRSS) was designed to collect issue-oriented (education) data quickly and with minimum response burden.

Providing the NCES with flexibility to hire additional statisticians would have several benefits, including equipping the agency with more experts to plan, conduct, and oversee critical statistical quality activities like data collection, design, administration, and analysis. Such flexibility would also facilitate the continuation of valuable education statistics programs and enable NCES leadership to optimize operations.

For problems relating to NCES’s level of authority and autonomy, legislation by the congressional authorizers (i.e., the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pension Committee and the House Education and Labor Committee) is needed. For instance, ensuring the NCES commissioner is both presidentially appointed and Senate confirmed, which has been recommended by leaders in the federal statistics and education research communities, should be a priority for the reauthorization of IES. The vehicle for this reauthorization is the 2002 legislation establishing IES, the Education Sciences Reform Act (ESRA). Due for reauthorization for many years, lawmakers planned to undertake ESRA in this Congress but the timeline for such work is now understandably uncertain due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

ASA Activities

The ASA has been actively addressing the NCES staffing issues for the past 18 months and the IES reauthorization changes over the past eight years. Paramount to this work is our partnership with the American Educational Research Association (AERA) and statistics leaders such as former Chief Statistician of the United States Katherine Wallman, former NCES Commissioners Emerson Elliott and Jack Buckley, retired NCES official Tom Snyder, and others who provide subject matter expertise and advice. The engagement of organizations such as the Population Association of America and Council of Professional Associations on Federal Statistics has also been constructive in conveying the importance of NCES and the need for its challenges to be addressed.

The ASA’s advocacy work includes meetings with congressional staff in both personal and committee offices, letters to leadership of congressional committees, and a request to meet with senior ED officials. Most recently, the ASA joined with AERA, Wallman, Elliott, Buckley, and former Chief Statistician Nancy Potok on a March 23 letter to congressional appropriations leaders urging that they address the NCES staffing issue and increase funding to the agency’s statistics line. The letter writers also spoke strongly against the proposals to transfer NCES assessment responsibilities to a new center and remove presidential appointment status of the NCES commissioner. Specifically, for the former, they wrote:

The data program of a modern government education statistics agency must cover a wide array of topics, just as those of health, agriculture, or other topical areas must. For education, examples include traditional areas such as how much money is spent, for what purposes, and how costs are borne by taxpayers. The statistical program also includes data on students enrolled and their characteristics. And it includes descriptions of the teaching resources available and how teachers are prepared. But the capstone measures are ones that inform the public about what students have learned. That information is of greatest help to the public when it can be associated with costs, teachers, and other aspects of education. Planning for the data collections, understanding how the data will be analyzed, and knowing what information the public and policymakers need to make informed decisions works best when the array of statistical studies are housed together and integrated. Among other things, that organizational arrangement will best facilitate making priority decisions across assessment studies and those in finance or demographics or teaching resources when tradeoffs must be made.

For the latter, they stated, “Senate oversight of the NCES commissioner appointment would help ensure a qualified leader and objective education statistics for our nation. Conversely, removing the presidential appointment of the commissioner could further weaken the ability to provide objective and credible statistical data.”

Attention to the NCES staffing issue increased after the previously mentioned Washington Post article, titled “Understaffing Threatens Work at Key US Education Statistics Agency, Experts Say.” The article quotes Larry Hedges, chair of the ASA Scientific and Public Affairs Advisory Committee, and reproduced the ASA’s joint letter with AERA and experts in federal statistics.

Through its science policy and advocacy efforts, the ASA developed three one-page documents to succinctly convey the value of NCES’s work, outline NCES’s staffing crisis, and highlight the ASA’s reauthorization priorities.

The ASA has also been working to raise awareness of the challenges facing NCES by communicating with other organizations and education-related coalition groups.

Similar to NCES, statistical agencies across the federal government are facing new and sometimes enduring challenges. Indeed, ASA Director of Science Policy Steve Pierson’s annual Amstat News article about the agencies’ budgets reported that nine of the 12 principal federal agencies (excluding the Census Bureau) have lost purchasing power since FY09, with several losing at least 10 percent.

To learn more about NCES, numerous resources are available. Visit NCES’s website, review the Amstat News Q&A with Commissioner James Woodworth, or read about NCES’s first 150 years.

This a very disturbing article. What we need now is more statistics to support and enhance rational decision making – not the reduction of quantitative information.